On August 6th, 1945, the United States detonated a 5-ton nuclear weapon over Hiroshima, Japan. The result helped end WW2 in the Pacific Arena as Japan surrendered less than one month later, but it was devastating to the city of Hiroshima and its immediate surroundings. Approximately 100,000 Japanese perished in the blast and about 5 square miles of the city were obliterated as ground temperature reached above 1800⁰ C in the firestorm that followed.

Continue reading Sand from HiroshimaTag Archives: sand collecting

A Sea of Garnet Sand

In early 2020, I was comfortably sitting in my man cave planning a September trip to collect beach sands along the coastline of southern New England. While cruising along the shoreline using Google Maps satellite images I spotted a bright red patch of beach near Madison, Connecticut. Zooming in, there seemed no doubt. The beach sand there is red. Could the dominant mineral in that patch of beach be garnet? If it is, this could be a highlight stop along the trip. Continue reading A Sea of Garnet Sand

Sand from a Swamp

In September, I met Leo Kenney at Plum Island in Massachusetts and later at his home northwest of Boston. And yes, we traded sands. One that I came home with intrigued me. It was labeled Floyd’s Island, Okefenokee Swamp, Georgia. From all appearances, it was fine-medium-grained quartz-rich sand, much like one you might find on an ocean beach. But this one was from a swamp. I needed to know more. Continue reading Sand from a Swamp

Utah sunstone

This month I was working with “sand” that was actually too large to be technically called sand. Rather the grains were granules, the finest size fraction of gravel. I had obtained 200ml samples of four different gravels from Ed Tindell, a Texas collector, trading him gravels from northeast locations I had visited. One of my new samples was from Sunstone Knoll in Millard County, Utah. The gravel had accumulated in the alluvium shed from adjacent Sunstone Knoll. Ed had size-sieved a large sample and the material he sent me was from the 1/16” to 1/8” (1.7-3.2mm) size range, bridging the upper limit of sand, but mostly fine gravel or granules (see chart at the end of the article).

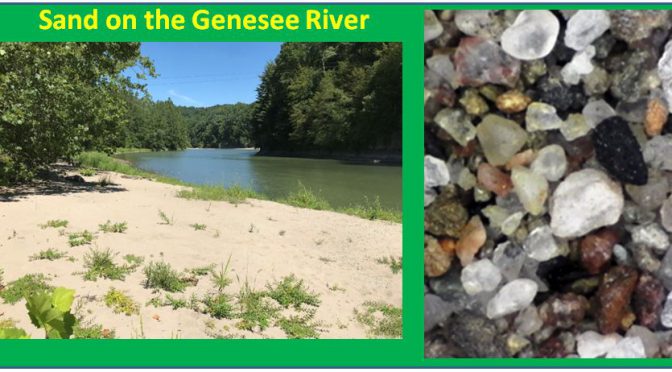

Collecting a River

The Genesee River ends in my hometown of Rochester, New York completing a 160-mile journey from Potter County, PA. During its course, the river falls some 2250’. Several notable waterfalls mark its journey north.

If you read my blog, you might know that I have become an arenophile, or more simply, a sand collector. In that endeavor, I have started to collect sand along the path of the Genesee River as it crosses across mostly rural farmlands and suburban communities. Rochester is the only major city graced by its presence. The surficial geology is mostly glacial deposits (moraines, outwash, etc.) of highly variable composition, but the river also cuts into Paleozoic sedimentary rock below that is Pennsylvanian to Ordovician in age, a rock record of about 140 million years. The major waterfalls mark resistant limestone and dolostone units; intervening shale units less resistant to erosion generate gentler topography.

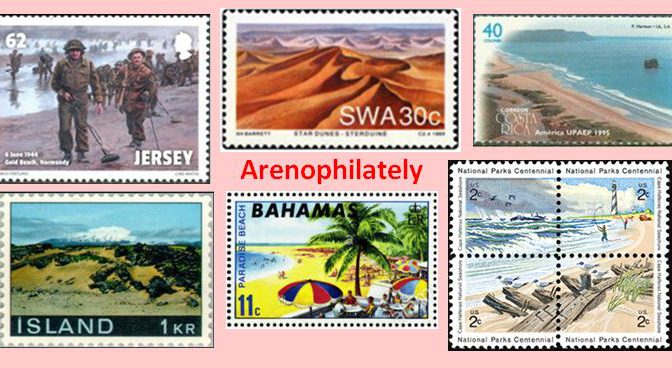

Arenophilately

I wrote this article for the Spring 2020 issue of Philagems, the newsletter of an International Group of stamp collectors with an interest in “Gems. Minerals, and Jewelry on Stamps.”

I have a confession to make. I have become an arenophile. Fortunately, in many places it is not illegal (unless trespassing while doing it), and it should not be harmful to my health. I would say it is generally not contagious, but I did catch it a year ago when introduced to the hobby at a local rock club meeting. I did not realize I was hooked until the summer of 2019. While collecting minerals on trips in Maine and Michigan, I kept my eyes open for sands to collect and proceeded to fill quart freezer bags at a few dozen locations along lakes, rivers, and from glacial deposits. You see an arenophile is a lover of sand. The word is derived from the Latin “arena” (sand) and the Greek ”phil” (love).

But this is a philatelic newsletter, what does this have to do with stamps, and more specifically minerals on stamps? Well, sand is nothing more than a pile of mineral grains, and there are certainly many worldwide postage stamps depicting sand. The most popular thematic stamps depicting sand are, of course, beaches, like several of those depicted in the header. But there are also river sands, land sand, and wind-blown sand dunes such as those on this South-West Africa (now Namibia) stamp, also in the header. Why not collect and display sands from various beaches next to stamps showing these beaches? And why not call it arenophilately? Would this not be a reasonable offshoot of a group specializing in minerals on stamps? There are actually some very unique and beautiful minerals hidden in the sands of the world. Continue reading Arenophilately

Heavy Sands, Hamlin, NY

Last July I collected one of my first sand samples, locating garnet-magnetite sands in a small cove east of Hamlin State Beach on Lake Ontario. It turned out to be one of the more popular trade sands I have and although I still had some I decided to venture out again this year. I was curious whether the accumulation would still be there, virtually one year later. Perhaps last winter’s storms removed the heavy sands and I might have to search anew. But they were right where they had been a year ago and even more stratified.

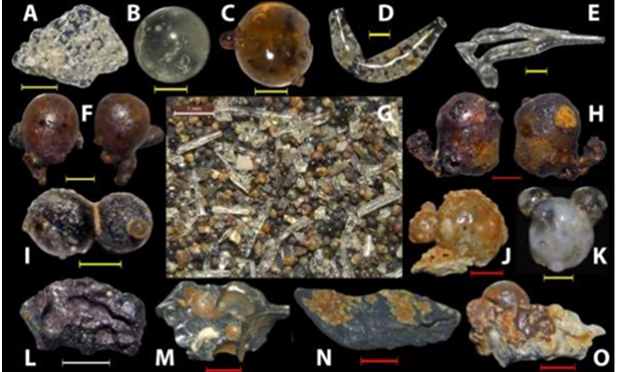

A Phosphatic Sand Beach

Some sand can be appreciated purely for its color and appearance. Other times the shapes of the grains or the overall texture of the sand makes it stand out when compared to others. Of course, a unique geology or an unusual mineral component can help to distinguish a sand also. Occasionally a beach comes along where the sand displays all three attributes. I consider the phosphatic sands from Caspersen Beach in Venice, Florida to be such a sand.

My First Sand?

It has now been almost a year since I started actively collecting and trading sand. I collected somewhere near 100 different sands last summer and fall during mineral trips or on day outings around western New York. And during the winter I have traded some of those for others. I think my total count exceeded 750 earlier this month when trade packages arrived from Maryland and California.

With that backdrop, imagine my surprise last January when my wife dug out three peanut butter jars from the corner of the garage labeled “Monahans Sandhills, 1995”. They were full of tan quartz-dominated sand! She had collected the quartz-rich sand when we had lived in Midland, Texas, some 50 miles to the east. She had earmarked them for our three sons and pretty much forgotten them (the sands, not our sons!).

Golf Course Sand

It is mid-April and I should be planning field trips, perhaps even taking my first of the season. But like everyone else I am planted at home, watching the first responders and others attempting to defeat this virus. But what else have I been doing? Well, first off, the yard and all the rock gardens may look as good as they ever have by the time it is warm enough for growth to begin. And I have been taking walks, lots of walks: short walks, intermediate walks, and long walks. I am wearing my walking shoes out. I know every nook and cranny of my neighborhood.

On one of those long walks in late March, I was thinking about the New England beach trip for sand collecting that I was not going to be able to undertake. And I happened to be walking along the edge of Oak Hill Golf Course in my home town of Pittsford, NY. I saw sand, lots of sand. Of course, I know that golf course sand is not local, nor is it 100% natural. Nevertheless, I did wonder what it looked like and where it might come from.

It Was Meant To Be

I should have known. It was only a matter of time before I would return to my roots and become a sand collector again. It goes back to December of 1976. I was a senior at Lehigh University with one semester left before earning a B.S. in Geology. I wanted to do a Senior Research project during my final semester. Having just completed a course in Sedimentology, Professor Bobb Carson suggested I study the heavy minerals present in beach sand. Perhaps I could compare the composition of heavy minerals present in the tidal zone with those high in the dunes. Perhaps aeolian sands would have a different heavy mineral content than those in the tidal zone. Why not, I thought. It could be fun.

Herkimer sand

On April 1st, Wayne County Gem and Mineral Club was planning to open its 2020 field season with a visit to Ace of Diamonds in Middleville, NY. The coronavirus has intervened with our plans and this annual rite of passage is not possible this year, but we can spend time enjoying the Herkimers we have collected on past trips.

For most folks these are small- or modest-sized crystals collected from the piles of rock the owners have hauled from their active, off-limits, mining area behind the hill. And I certainly spend time digging and breaking large rocks in search of centimeter or inch-sized diamonds. But, when the club visited last October, just before the site went into its annual hibernation, I did something a bit different.

Blue Sand from California

Sand comes in virtually all colors, however, as my collection grew this past year, I was not adding much blue to my collection. In fact, I really did not have a blue sand until a very unique and interesting sand appeared in the trade box that Bill Beiriger sent me in January. It was inauspiciously labeled as fine, blue-gray sand from a location 12 miles east of Livermore, California. The GPS coordinates Bill provided placed the site closer to Tracy, California and in the Diablo Mountain foothills.

Bumpus Brook Sand

It seems many sand collections focus on ocean beaches. This is understandable. The settings provide gorgeous destinations and the sands can be wonderfully textured. I like beach sands, but don’t want to short-change river sands in my collection. Unlike beaches, where provenance is hard, or even impossible, to define, river sands offer an interesting opportunity as their provenance can be determined. Naturally, this is not easy if your sample comes from the Mississippi River delta but consider the other extreme, a sand sample from a mountain stream.

Last July, I traversed the White Mountains of northern New Hampshire on a return trip from Maine. Just off Route 2 north of the Presidential Range is a short, 3 mile (5 kilometers) drainage between two ridges on the steep north slope of Mt. Madison. It is called Bumpus Brook and a small bridge along Pinkham B Road allows access. Much of the creek’s sediment load is larger than sand size with cobbles and small boulders strewn along the flowing stream. But, at bends on both sides of the bridge, there are sand bars that can be sampled.

My Backyard Sand

About 12,000 years ago, pro-glacial Lake Iroquois occupied all of the current Lake Ontario and extended significantly south and east into New York. The glacial ice was retreating but had not yet melted far enough north to expose the St. Lawrence Seaway, forcing the significantly larger Lake Iroquois to drain east through the Mohawk Valley and then south along the Hudson River. All of Rochester, NY was beneath this lake.

Arenophilia

I have a confession to make. I have become an arenophile. Fortunately, it is not illegal (unless trespassing while doing it or if you are in Sardinia), and it should not be harmful to my health. I would say it is generally not contagious, but I did catch it this past spring when Jim Rienhardt introduced us to the hobby in the Wayne County Gem and Mineral Club November 2018 newsletter and later at the March meeting. I did not realize I was hooked until this summer. While collecting minerals on club trips to Maine and in Michigan, I looked for sands to collect and proceeded to fill quart freezer bags at a few dozen locations along lakes, rivers, and even from glacial deposits. You see an “arenophile” is a lover of sand. The word is derived from the Latin “arena” (sand) and the Greek ”phil” (love).

Hamlin State Beach .. and garnet sand

Last March, Jim Rienhardt brought his collection of some 270 sands to the WCGMC meeting and told us about arenophiles (sand collectors) (Reinhardt, 2018). Jim repeated his presentation at the Rochester Academy of Science later that month. At that meeting RAS member Paul Dudley brought along some sand he had collected from Hamlin State Beach some 50 years ago. Paul’s sand was red and dominated by garnet, but full of other heavy minerals. He told us that the sand had been collected during a college field trip late in the spring when Lake Ontario first started to recede from winter highs.

I parked that in my memory and on my calendar and on July 8th set out to find some “garnet” sand for myself. I was not disappointed. The first stop I made was at Area #5 at the west end of Hamlin State Beach. The Lake level seemed to have dropped, perhaps a foot from its highest erosional cut. And in the bank left when the lake level was highest was a 2-3 cm thick band of black and red sand. I sampled and took pictures and moved to other areas of the park.