Last March, Jim Rienhardt brought his collection of some 270 sands to the WCGMC meeting and told us about arenophiles (sand collectors) (Reinhardt, 2018). Jim repeated his presentation at the Rochester Academy of Science later that month. At that meeting RAS member Paul Dudley brought along some sand he had collected from Hamlin State Beach some 50 years ago. Paul’s sand was red and dominated by garnet, but full of other heavy minerals. He told us that the sand had been collected during a college field trip late in the spring when Lake Ontario first started to recede from winter highs.

I parked that in my memory and on my calendar and on July 8th set out to find some “garnet” sand for myself. I was not disappointed. The first stop I made was at Area #5 at the west end of Hamlin State Beach. The Lake level seemed to have dropped, perhaps a foot from its highest erosional cut. And in the bank left when the lake level was highest was a 2-3 cm thick band of black and red sand. I sampled and took pictures and moved to other areas of the park.

Most beach or river sand is quartz-rich with a feldspar component. These light-colored minerals are the most common rock-forming minerals that survive the processes of erosion. Quartz and feldspar have a similar density and tend to accumulate together when continually reworked by water. Heavier minerals (like garnet, magnetite or GOLD) that are weathered to sand size tend to separate from the lighter quartz and feldspar and it was layers of these heavier minerals that I was seeking.

The primary areas to the east and within the park seemed to lack heavy sand accumulations, but I really struck it “rich” when I stopped just east of the park. No, not gold, but at a small beach-like location adjacent to the Monroe County Water Authority property on Newco Road, I found a beach surface that was glittering with red sand. And, as at Area 5, I could find the source unit in the bank where the lake must have crested. This time the unit was at least 6 cm thick and I could use my sampling spoon to extract garnet-rich sand.

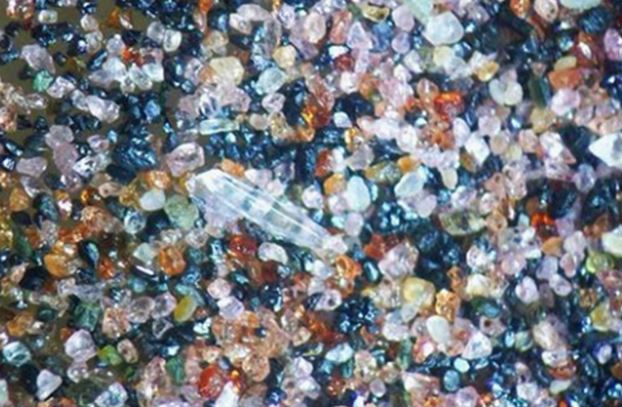

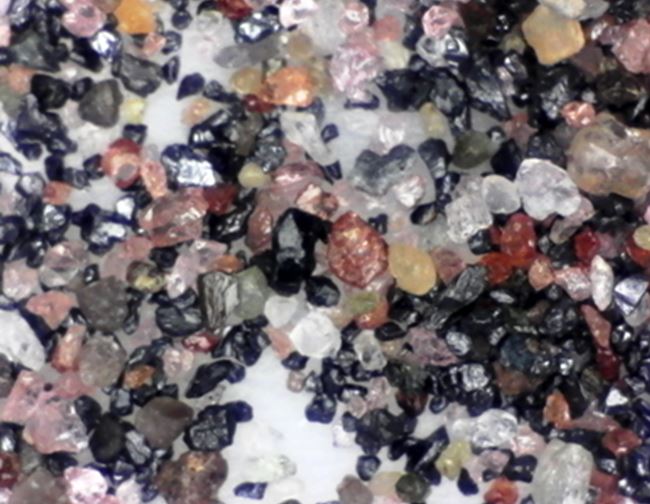

Both sand photographs were taken with a zOrb 65x digital microscope. Sand is fine-grained (100-200 microns, 0.1–0.2 millimeters).

Although both sands contain a lot of garnet, there was a clear difference in the associated heavy minerals. A significant component of the sand from Area 5 was magnetite and the sand could be scooped out with a magnet just as easily as with the spoon. This was not true with sand from the Newco Road location. There were black minerals in that sand, but very few grains were magnetic. In fact, I had to search to find any magnetite in that sand.

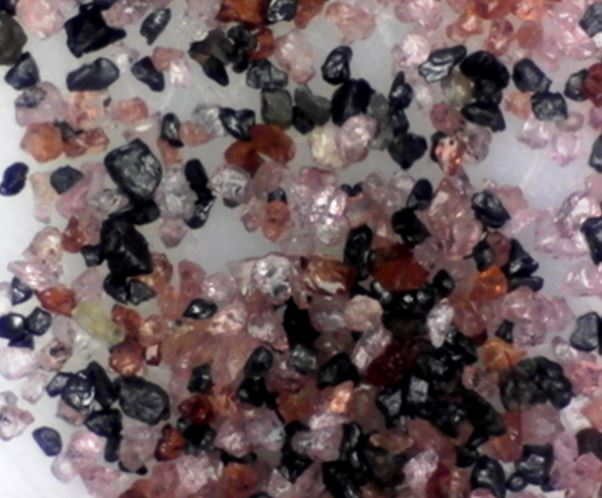

You might be asking how did the garnet sand get concentrated into layers? Heavy minerals (almandine garnet has a specific gravity of 4.2 or approximately 60% denser than quartz), accumulate in low-energy environments where repeated washing strips lighter components. On a beach, this typically occurs in the “swash zone”, where the surf washes across the beach face and loses energy. After sufficient time a lense of heavy mineral can deposit and if the water level then drops (as it finally is doing at Lake Ontario), the heavy minerals are stranded until such time as they are exposed by an even higher water level.

The recently washed surface depicted on page 1 from Newco Road shows this stranded washed surface covered with garnet and heavy black minerals. My picture does not do justice to how brilliantly red this surface was in the bright sunshine. It is interesting that the wave action not only separated these heavy minerals from the more common quartz along the beach, but it also separated the red almandine and the black minerals in streaks across the undisturbed surface.