Knapping is the shaping of flint, chert, obsidian or other suitable material through the process of chipping off small pieces, thus shaping the piece into a desirable tool, weapon, or work of art. The process takes advantage of the fracture style of cryptocrystalline quartz and glass. Lacking cleavage or any natural weaknesses quartz fractures along smooth curved surfaces which often come to very sharp edges. This property is called conchoidal fracture.

Whether knappers are generating an arrowhead, a knife or just a colorful ornamental piece, they will seek to generate regular scalloped surfaces around the piece. In addition, if the product is an arrowhead or tool, they strive to create a linear sharp edge where the conchoidal fractures come together..

There is a diverse set of knapping tools that can be used depending on the nature of the stone and the skill of the artisan. Hard hammering with a piece of quartzite or other hard material can be used to chip off large flakes and prep a stone for more detailed work. Softer hammering tools allow for more control and for knapping smaller and thinner pieces. Tools with copper or brass tips are used to apply a sharp and sudden force to a desired location of the stone. This is referred to as pressure flaking. The angle of contact and the directness of the strike are critical to generating the desired flake.

I knew practically nothing about knapping when I attended the Stone Tool Craftsman Show, but hoped that I could learn a bit about the various cherts in New York that the Native Americans used and that modern craftsmen seek for their art. Turns out there are multiple suitable chert units in the Paleozoic Era sedimentary rocks of New York.

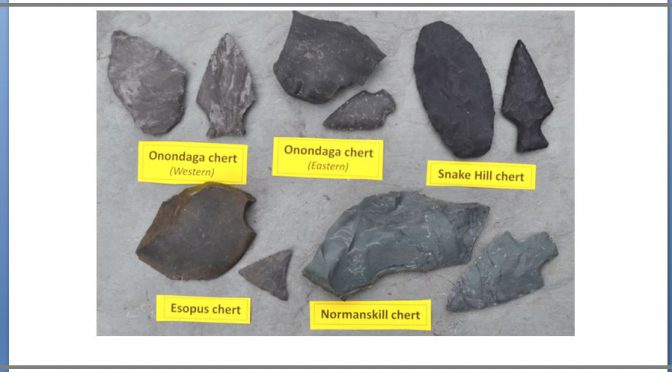

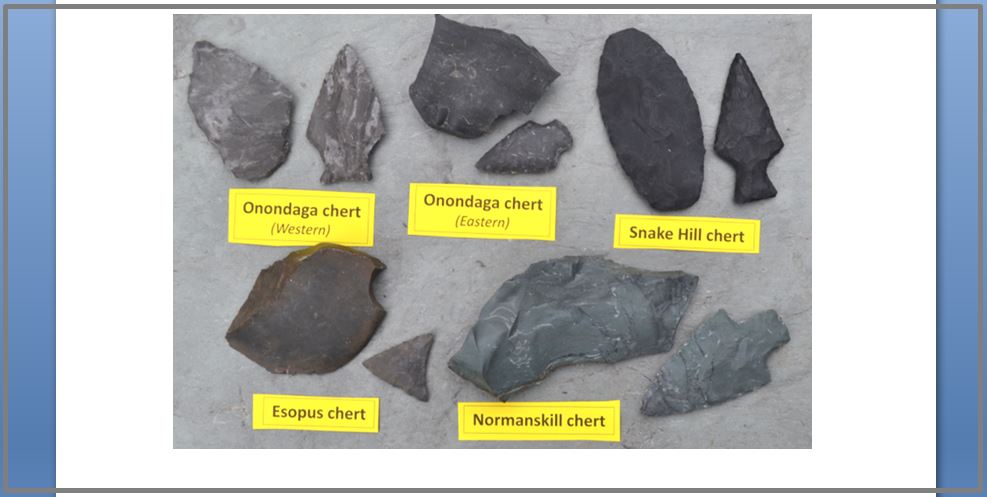

The most prolific of these cherts, and the only one I had knowledge of before attending, is the Devonian Onondaga chert. But I did not know that there were Eastern and Western varieties. Western cherts from our region are quite clean and knap well although they can contain small dolomite rhombs and occasional pyrite. Sometimes they have gray streaks that offset the blacker color of the main stone. My arrowhead (next page) has gray streaks that add to its appeal. Eastern cherts are virtually isotopic (uniform in all directions) but can contain chalcedonized fossils and other impurities. Knappers seek chert that lacks impurities except for color variation.

Speaking of color, most New York cherts are quite dark, gray or almost black. The Onondaga cherts are affectionately referred to as “Stinky chert” because they contain residual hydrocarbon material that is released when they are knapped.

The Ordovician Normanskill Chert of eastern New York is also sought by knappers because it has a dark greenish color and often displays banding that can be worked into the piece. However, the green color is caused by small amounts of clay that has been converted to chlorite during metamorphism which can interfere with the knappability of the chert. There are several known old quarry sites for Normanskill chert in the southeast portion of New York State. Mike McGrath believes that the Normanskill Chert is the most beautiful knappable material in all of New York State.

Another New York chert that is frequently used by knappers is the Esopus chert found in the southeastern part of the state. This Devonian chert can be laced with seams adding to its character, however my raw piece and small point are uniformly dark grey.

The final example of New York chert I was able to obtain was from the Ordovician Snake Hill Formation in Saratoga County. These cherts are very black and were deposited in a shallow marine basin adjacent to the Taconic highlands.

References:

McGrath, M, 2006, Flintknapping,, website: http://www.susquehanna-wd.com/susquehanna_wd_home_page.html

Prothero, D., and Lavin, L, 1990, Chert petrography and its potential as an analytical tool in archeology, GSA Cent. Vol. #4, p. 561-584.