The annual test of aging bones and muscles that we call the Wayne County Gem and Mineral Club quest for really old Ontario rocks was in July this year. The event lasted five days for several and eight days for four of us who continued on to Cobalt, Ontario. I am happy to report that all of us survived, and we have the pictures, stones, bruises, and mosquito bites to prove we were there. The whirlwind trip included collecting beryl and rose quartz in two pegmatites, a day in Eganville for apatite and biotite, a quarry stop for fossils, Princess Mine for sodalite, Schickler Mine for fluorite, Desmont Mine for mosquitoes, and Essonville Line roadcut for fluoro-richterite. Four of us carried on to Cobalt, grabbing some garnets along the way and finding one very nice silver-laced boulder at a mine dump in Cobalt.

The highlight of the trip had to be the day we spent with Canadian collector George Thompson on his mineral claims off Gibson Road in Tory Hill. We all thank him for sharing his calcite vein-dikes with us and allowing us to carry home memories of a fine day in the field. Oh, we took home some minerals also. And thus this note focuses on George’s property and the fifth day of our adventure.

Friday – July 21st, 2017: The day started like all others. The alarm clock rang at 6:30; we stumbled for coffee and breakfast and woke up while driving. At location, we piled out of the vehicles, strapped on our boots, collected up the requisite tools, and applied a few ounces of Deep Woods Off, while discussing what percentage of DEET we prefer. Mine was 25%. Then, on this fateful day, we struggled to follow George Thompson (whom we had met in Tory Hill), as he blazed a trail (well, sort of a trail) through the underbrush and over the small ridge to a multitude of pits and trenches on his claim.

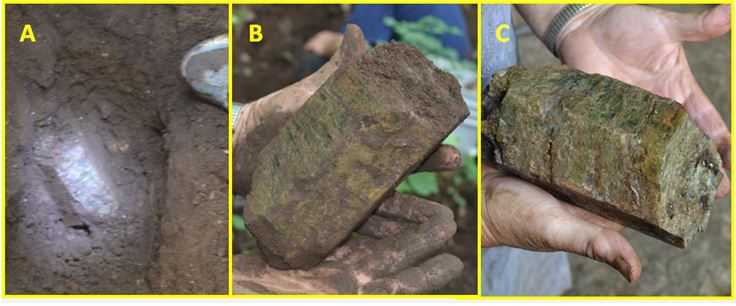

George showed us each of his trenches as proudly as one introduces folks to their kids. He showed us a 10’ deep natural trench lined with huge feldspars and amphiboles. A couple of us even dared to venture in (not me). Getting in was not difficult, getting out was, well, not so easy.

Most of the trenches/pits run parallel to each other. Some extend for tens of meters. It is likely that their direction records the dominant stress direction at the time of emplacement of the vein material. But as George explores his claims, he is learning that there is a second direction of mineralized veins, the dominant one that most of the digging has been done on and a second narrower system that intersects the main veins at an acute angle. He theorizes that some of the more exotic and perhaps interesting mineralogy may occur at these intersections. More digging will help him figure some of that out. We obliged and dug all day, ostensibly contributing to his assessment of the property!

Actually, the veins themselves are not any different from features that occur throughout the Grenville Geological Province of the Bancroft, Ontario region (Joyce, 2006). We had collected in similar features near Eganville and at the Schickler Mine earlier on the trip. The linear mineralized features have been called “calcite vein-dikes” because their origin remains unclear. Are they typical calcite vein deposits from hydrothermal fluids or are they some sort of carbonate-rich melt that would be better classified as having an igneous origin, almost a sort of carbonate pegmatite? For the time being we will leave that discussion for others to ponder. We went to collect them!

Given their mineralogical variation across the province it seems likely that whatever the origin they did leach elements from their host rock, itself a potpourri of rocks including marbles, gneisses of variable composition and granitic rocks. This variation in host rock likely influenced the variety of minerals encountered. In addition to calcite, the dominant minerals in George’s vein-dikes are feldspar and amphiboles. But sprinkled between the large crystals are many apatites, an occasional titanite, and probably some other goodies.

Amphiboles are darn near impossible to identify from each other in the field, but given that Joyce (2006) reported Bear Lake amphiboles with similar habit to be fluoro-katophorite, I may label mine accordingly until proven otherwise. Most of the amphiboles encountered were somewhat or completely etched, although Glenn dug into an area where there were lustrous and terminated crystals.

For those with an inquisitive mind, fluoro-katophorite is a sodium-calcium amphibole:

Na(CaNa)(Mg4Fe3+)(AlSi7O22)F2

The Bear Lake Diggings is the type locality for the species.

References:

Adamowicz, M., 2013, Searching for crystals in the Calcite Trenches at Bear Lake Diggings, Ontario, Mindat article – LINK

Joyce, D. K., 2006, Calcite Vein-Dikes of the Grenville Geologic Province, Ontario, Canada, Rocks and Minerals, v. 81, p. 34-42.