Garnet mining in New York State dates back to the late 19th century when the Barton Mine first opened in 1879. Henry Barton experimented with garnet as a harder and more durable abrasive than simple sand and after a fisherman friend told him about the prolific garnets in the Adirondacks he staked his claims and went into production (Kelsey, 2015).

Two decades later, in 1898, Frank Hooper started excavating garnets from a hill slope one mile east of Thirteenth Lake in North River, NY. Unfortunately, his garnets were not as large and not as concentrated and he could not compete with the Barton Mine. The story is that Hooper ended up working at the Barton Mine. Although the Barton Mine area was moved to adjacent Ruby Mountain in 1982, Barton Mines Inc. has been continuously producing industrial-grade Adirondack garnet for over 130 years.

But this is about the Hooper Mine, the lesser-known, overgrown escarpment/quarry where Mr. Hooper tried his hand at mining over 100 years ago. The site is best accessed from the parking lot area of the Garnet Hill Lodge. The proprietors at the lodge are happy to allow visitors access via their system of cross-country ski trails that crisscross the hillside. Just check-in at the lodge first; they even can provide directions and a map. And lunch when you have had your fill of garnets and black flies! It is about a 1200’ walk up a gentle slope to the mine. Translation, it is downhill when carrying garnet to the vehicle.

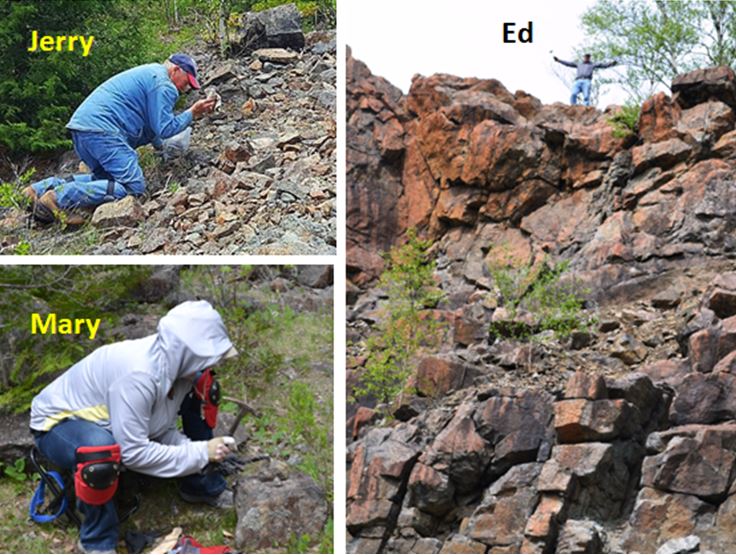

This May, I made this trek on a wonderful spring day full of sunshine and black flies. The former was most appreciated; the latter were a complete nuisance. With buckets, backpacks and insect repellent we made our way up to the man-made escarpment in search of garnet treasure. Once at the old quarry site, there is no problem finding garnets. They are literally everywhere and almost any rock you turn over or peck with a hammer is full of 1-3 centimeter sized garnets.

The problem becomes distinguishing pieces worthy of the downhill carry from all the leaverite. Want a nice twenty-pound metamorphic rock with multiple large garnets for your garden? Well, there it is, heck there they are, just carry them out. Want 200 tennis ball-sized specimens of garnet gneiss to give to youngsters or to fill club grab bags? Just pick them up and put them in your bucket. But if you want a shiny dodecahedral one-inch garnet on matrix then you may be there a while looking. Museum pieces are few and far between. In fact, they may not exist.

Warren County garnets are generally considered to be of almandine composition, with iron and aluminum occupying the cation positions in the lattice, but there is appreciable pyrope content (magnesium replacing iron) and also some grossular (calcium) component. For a full description of the chemistry and mineral structure of garnets, see Garnets Galore in the January 2016 WCGMC newsletter.

Although the garnet surfaces are typically altered and the large crystals themselves are internally fractured they still make for attractive rocks given the size and color of the garnet. Although one of the primary minerals in the Hooper Mine host rock is hornblende, the garnets at the Hooper Mine do not have the attractive black hornblende halo that is associated with the large garnets from the Barton Mine.

References:

Kelsey, M., 2015, Mine Ramblings in the Adirondack Park’s Garnet Woods, blogsite