Written for the February, 2015 WCGMC News

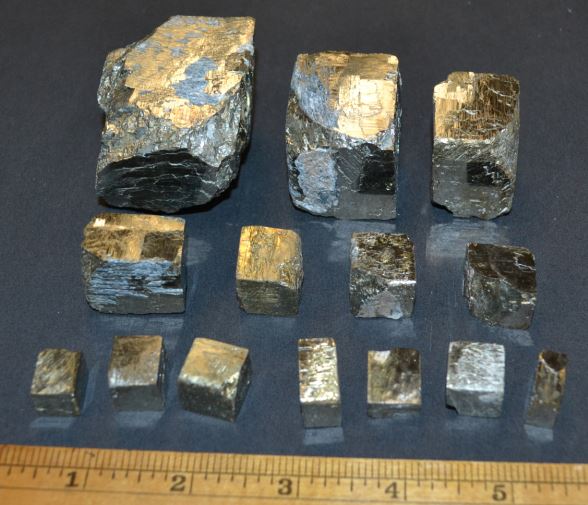

The month’s site article is leaving New York again and is headed for the Piedmont region of North Carolina. No, not because it is necessarily warmer there, although it probably is, but because I am the editor and I decided it would. But seriously, who doesn’t like pyrite cubes and when I discovered some in a bucket in the Weiler’s barn/club workshop last month I asked where they were collected. Turns out they came from the Standard Mineral Company Mine in Glendon, North Carolina. WCGMC had ventured south on at least two occasions (2009 and 2010) to dig pyrite on trips organized by the Mountain Area Gem and Mineral Association (M.A.G.M.A.) of North Carolina.

It sounded like an excellent opportunity to revisit some club history. And then I got really lucky. A visit to the M.A.G.M.A. website yielded photographs from those trips and bingo there was Bill Chapman in his orange collecting uniform holding up a 2” pyrite cube for all to see. The gentleman just behind his right shoulder is Bill Lesniak. I considered this is clear proof that they had actually made the trip south and I set off to learn something about the mine.

Photo from M.A.G.M.A. website

First, I learned that Standard Mining Company is not interested in the pyrite. Rather they are mining pyrophyllite, an industrial mineral that is primarily used in ceramic formulations due to its excellent thermal stability. It also has applications in insecticides and in brick making. The pyrophyllite mines in Moore County, NC have been in operation for over 150 years.

The open-pit mine in Glendon exploited a lens of relatively pure pyrophyllite that ranged from 100-300’ wide, extended perhaps 1000’ on strike and was tilted at about 45 degrees. As pyrite was an undesirable impurity for the miners, the layers richest in pyrite, which paralleled the purer unit, were not removed and have been targeted by collectors whenever the mine owners have permitted clubs like M.A.G.M.A. to organize digs.

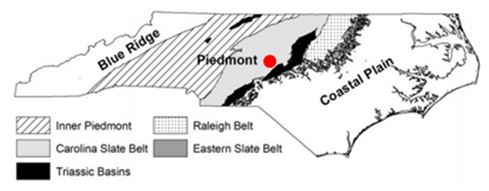

The pyrophyllite deposits occur in the Carolina Slate Belt in central North Carolina. The name is a bit of a misnomer as there is not much slate around. However low-grade regional metamorphism has imparted a slaty cleavage to much of the rock in the region and the name persists. The rocks, however, are dominantly of volcanic origin and about 550-600 million years old. They were detached from North America some 500-400 million years ago only to become re-attached about 300 million years ago (Rogers, 1999) as part of the Alleghanian mountain building period, the third and final mountain building event of the Appalachian Mountains.

But the story of the pyrophyllite is more complicated than just migrating crust and continental collisions. Pyrophyllite is Al2Si4O10(OH)2. Large and pure deposits of the aluminum sheet silicate are not particularly common and require a fairly unique geologic history. First, hydrothermal alteration within the volcanic rocks must act to leach other elements, like potassium, calcium and sodium from feldspar. This leaves a high aluminum, high silica rock, but at the near surface conditions where widespread leaching can occur the product would be a clay mineral like kaolinite.

To generate pyrophyllite requires a second event. The leached rock must be buried deeply enough to undergo metamorphism. At temperatures of 350-400ºC and about 2 kilobars pressure (or at 6-8 km) pyrophyllite and quartz become a stable mineral assemblage (Sykes and Moody, 1978). This level of metamorphism, termed “greenschist”, occurred when the Slate belt region was plastered onto the North American plate and buried in the aforementioned Alleghanian orogeny (mountain building event) some 250 million years ago (Rogers, 1999).

Of course, a third event is necessary also. The metamorphosed rocks must be exhumed by erosion. And this is exactly what has been happening for the last quarter of a billion years in central North Carolina as the core of the Appalachians and the Piedmont is being slowly exposed.

OK, that is fine, but what about the wonderful pyrite cubes that can be extracted from the weathered zones which parallel the massive pyrophyllite? Well, they too owe their existence to the hydrothermal event that leached the original volcanic rocks. Anyone who has visited Yellowstone or Lassen National Parks is aware that sulfur is a common component of hydrothermal fluids. In addition, iron can be released by the leaching of any mafic (iron-magnesium) minerals in the rock. If the pair combine in a low oxygen environment pyrite can be produced, either during the original hydrothermal activity or during the metamorphism that followed.

Another interesting element that can be concentrated in volcanic fluids is fluorine (F). Although not common in the slate belt pyrophyllite occurrences, lucky collectors can be rewarded by finding brilliantly purple fluorite hiding in vugs in the metamorphosed volcanic rocks. If the WCGMC members who ventured to Glendon in 2010 found any fluorite they are holding out on me. And they all know fluorite is a favorite of mine! Maybe we need to see if we can get back to the Carolina slate belt, perhaps on the way to the Lower Mantle for bridgmanite?

Photo from M.A.G.M.A. website and 2012 field trip.

References:

M.A.G.M.A. website, 2010, visit field trip page http://www.wncrocks.com/magma/magma.html

Rogers, J.J.W., 1999, History and Environment of North Carolina’s Piedmont, published by J.J.W. Rogers (http://www.geosci.unc.edu/files/documents_PDF/piedmont_hist_env.pdf

Rogers, J.J.W., 2006, The Carolina Slate Belt, in Stone Quarries and Souring in the Carolina Slate Belt, Research Rept. #25, UNC Res. Lab of Archeology, 15 p.

Sykes, M.L., and Moody, J.B., 1978, Pyrophyllite and metamorphism in the Carolina slate belt, Amer. Min., v. 63, p. 98-108.