Porphyroblast: I’ve always thought that was such a neat word, maybe even interesting enough for a story. Say it out loud three times (“pore-fur-o-blast, pore-fur-o-blast, pore-fur-o-blast”). Now don’t you want to learn more, perhaps even own a few?

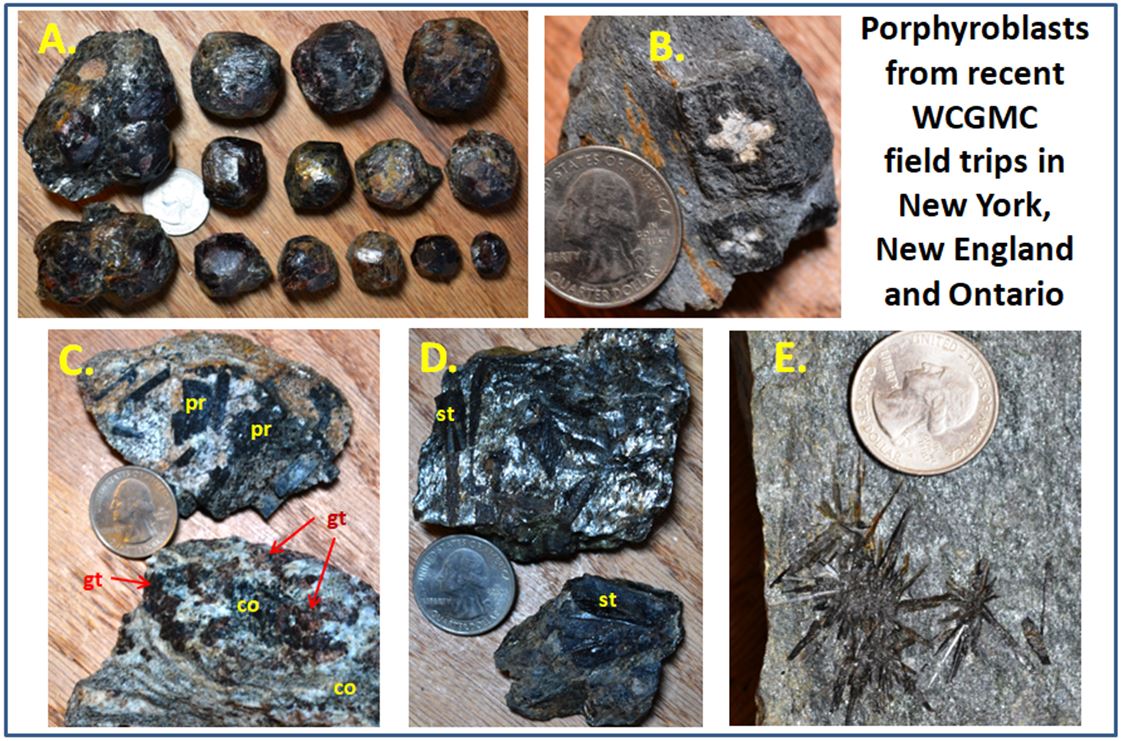

Porphyroblasts are those large recrystallized minerals that grow in the groundmass of a metamorphic rock, most typically in schists and gneisses. In New York State, we immediately think of the bright red almandine-pyrope garnets in the gneissic rocks in the Gore Mountain area, but the truth is the metamorphic schists and gneisses throughout New York and New England often contain garnet porphyroblasts. Unfortunately a lot of New York’s garnets are hosted in high-grade metamorphic gneiss and they don’t display crystal faces when the rocks are broken. Nevertheless they are large, colorful and fun to collect.

When garnets grow in mica-rich schists, they are more likely to expose the familiar parallelogram faces characteristic of dodecadehedral crystals. Or if the faces are hidden, muscovite or biotite can be removed to expose them. In recent years, WCGMC has visited a site in River Valley, Ontario to bring home almandine garnets hosted by a biotite schist that is pretty itself. The surfaces of those garnets are somewhat “keyed” as they grew into the host biotite, but they are highly reflective. In November of 2017, WCGMC members visited the Little Pine Garnet Mine in North Carolina where perfectly formed almandines are set in a chlorite-chloritoid schist. The green chloritoid crystals are actually porphyroblasts too.

Probably the second most common and popular porphyroblast among collectors is staurolite. There are numerous sites to collect staurolite in New England and WCGMC has been to a couple of them in Middlesex County, Connecticut. Staurolite has a propensity to grow in very attractive twinned crystals, which are commonly referred to as “Fairy Stones”. There is even a state park in extreme western Virginia know as Fairy Stone State Park where twinned staurolites weather from the host rock and surface collecting of these crystals is permitted.

Other minerals that grow as porphyroblasts include tourmaline, hornblende, kyanite, andalusite, and cordierite. I mention tourmaline because WCGMC collected a really neat occurrence of metamorphic tourmaline in Chester, MA last summer, slender black dravite growing in a fine groundmass of corundum and magnetite (which is emery).

Another interesting metamorphic occurrence that I have visited occurs along the Moose River in the southern Adirondacks. Blue-grey cordierite occurs with the garnet there. Gem quality cordierite is called iolite; unfortunately no gem quality material in the Adirondacks! But, that same gneiss does contain a relatively rare porphyroblast. Prismatine is a complex magnesium-aluminum orthorhombic silicate that occurs as long black bladed crystals that resemble tourmaline, but are not!

Geologists can study the assemblage (or group) of metamorphic minerals present and use this to predict the temperature and pressure of the metamorphic process, perhaps the burial depth and therefore the amount of erosion that has occurred to bring them to the surface for us to collect. The chemical composition of porphyroblasts and the other minerals in the matrix provide evidence of the type of rock that was metamorphosed.