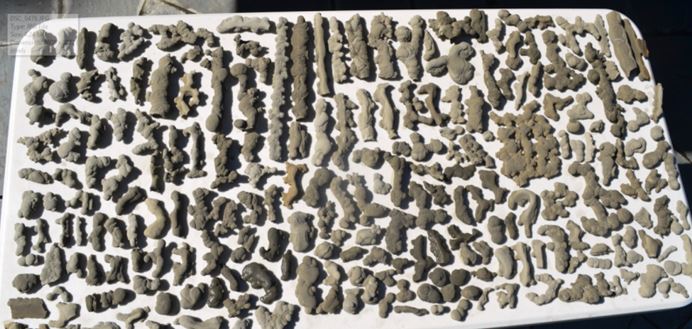

About 15,000 years ago the final of four glacial advances stopped in central Connecticut and a large end moraine was established. As the glacier retreated a large lake formed in what would become the Connecticut River Valley. Varved (seasonal) clay/silt layers were deposited. Debris (fossils, sticks, leaves, etc.) carried in with the clay/silt became nucleation points for calcite cementation and concretions grew in the clays. These unique concretions are now being exposed by erosion. The locals call them “Fairy Stones” or “Mud Babies”.

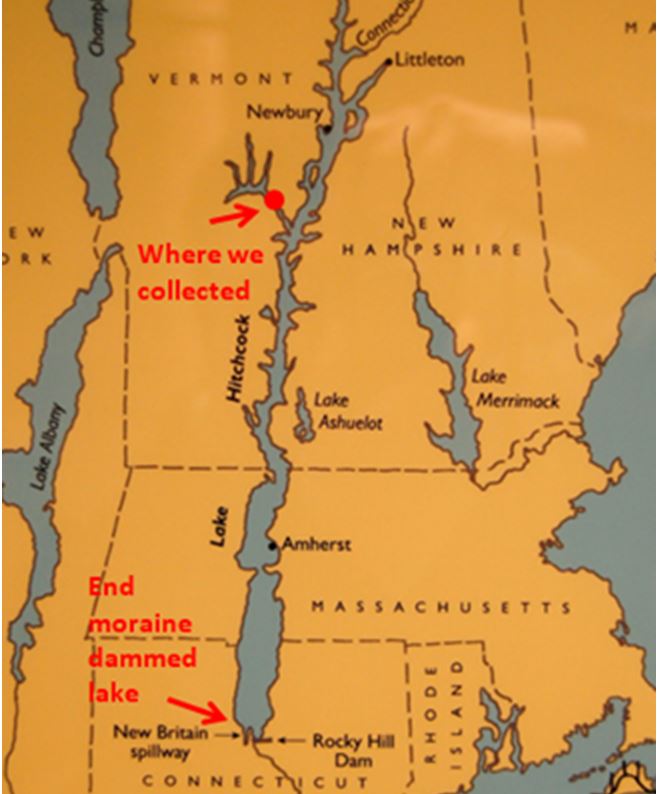

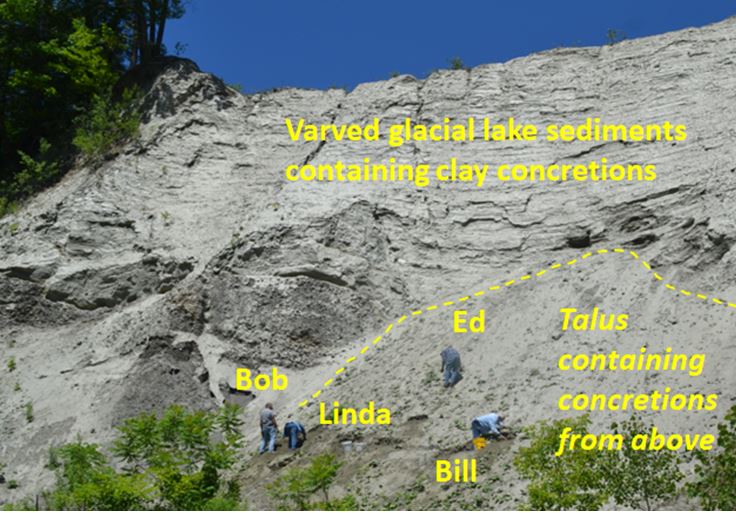

Several members of Wayne County Gem and Mineral Club decided to visit a site along the White River in Sharon, Vermont in search of these “Fairy Stones”. There are apparently a number of locations where they can be harvested from the weakly lithified clay-rich ancient lake deposits. We learned about one from Cristofono (2014). Armed with supportive information from two New England Clubs and with permission from the land owner we left a day before the June club trip to western Massachusetts to check out the site.

The varved lake deposits consist of alternating layers of fine silt and clay. Glacial run-off into the lake was full of silt and suspended rock flour produced by the grinding erosive action of the ice. Each summer “coarser” silt units were introduced to the lake and deposited. During the winter when the lake froze over, the suspended fine clay and rock flour slowly settled to the bottom. The resulting varves can be counted like tree rings. Their variable thicknesses permit geologists to correlate varve sequences up and down the Connecticut River Valley. Careful description, detailed mapping and radiocarbon dating of these varves provide insight into environmental and climatic changes for much of the 2500 year period during which the glacier retreated and the lake evolved (Ridge and Larsen, 1990). .

The concretions within the varved clays are both interesting and prolific. They apparently formed in the coarser silt units that were deposited each summer. In contrast to the clay units, the silt sections contained abundant decaying organic debris (leaves, sticks, etc.). Ground water flow when the sediments were buried just a few meters would have been focused along the siltier, more porous and permeable portions of the varves (Rittenour). The interesting shapes of the concretions likely reflect the nature of the organic matter upon which the calcite nucleated. The porosity of the silt was filled by calcite cement creating the concretion.

I had reservations that the concretions might be fragile or otherwise hard to protect/preserve. However, those thoughts were unwarranted. We loaded them gently into buckets and pushed them into the far recesses of our vehicles and proceeded with the rest of the 5-day trip. Once home they only needed a quick rinse to remove loose clay and expose the cemented concentric concretions. Because we collected in the weathered talis some were broken, but many appear to be complete.

The Sharon site, and apparently others along the White River, are on private property. Permission to collect should be obtained prior to visiting.

References:

Cristofono, P., 2014, Rockhounding New England, A Falcon Guide, p. 131-132.

Ridge, J. C., and Larsen, F. D., 1990, Re-evalulation of Antevs’ New England vare chronology and new radiocarbon dates of sediments from glacial Lake Hitchcock, GSA Bulletin v. 102, p. 889-899.

Rittenour, T., Glacial Lake Hitchcock, web entry