Have you ever heard of flint knapping? Do you know there is an active group of flint knappers in western New York and they hold their annual Stone Tool Craftsman Show every August? In 2018, the event is August 24-26 in Letchworth State Park, itself a geological wonder worth visiting. For three days members of the Genesee Valley Flint Knappers Association display their wares and share advice on knapping at the Highbanks Recreation Area in the park.

Visitors to the Stone Tool Craftsman Show can see flint knapping demonstrations and learn about a variety of other skills that helped prehistoric cultures survive. In addition to learning about the making of arrowheads, spears, and stone knives, the group holds several athletic competitions involving stone throwing weapons.

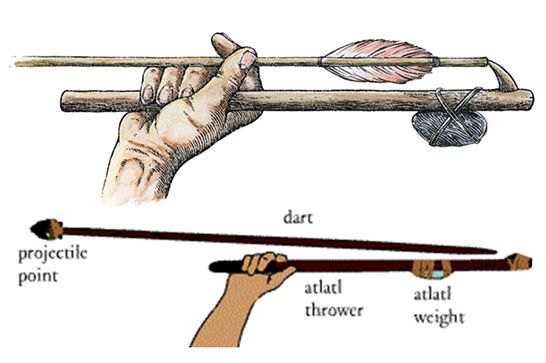

Have you ever heard of an atlatl? These primitive weapons allowed hunters to throw a stone projectile (often flint) hundreds of feet at speeds that can exceed 100 mph. You can see atatl demonstrations and even competitions among some of the best modern-day atlatl users in the country. Learn more about this 3-day event at the Genesee Valley Flint Knappers website.

But I am not a flint knapper (at least not yet!) and I want to talk a bit about the rocks used in knapping and the local source of such rocks in New York State. A purist may wince when hearing the term flint used in association with most knapping rock. By the original strict definition, flint is chert (or chalcedony) that forms during early diagenesis as silica-rich fluids pass through chalk sediment while it is being lithified. There are chalk beds throughout Europe (i.e. white cliffs of Dover in England), but nearly all chalcedony being knapped in the eastern United States is not formed in chalk. As such it is more properly called chalcedony or chert. But chalcedony knapping just does not have the ring to it, does it?

Consequently, the term flint has become more or less accepted, even by geologists, as a valid name for microcrystalline quartz material formed in all limestones (not just chalk), and sometimes even in other sedimentary rocks. This has led to the naming of geographic regions such as Flint Ridge in central Ohio. The multi-colored chert (or “flint”) from that region was prized by Native Americans for its color and knapping quality and continues to be sought after from the same reason.

The best chert/flint for knapping is consistent in its toughness and grain size and lacks any inclusions (Long, 2004). Small vugs due to mineral dissolution also detract from a stone’s knapping value. In western New York, the most prolific chert-bearing unit is also the most favorable for knapping. The Onondaga Formation is a gray Middle Devonian limestone that was prone to the formation of dark gray to black chert nodules during lithification. The host Onondaga limestone is also a preferred construction stone and is quarried across western and central New York.

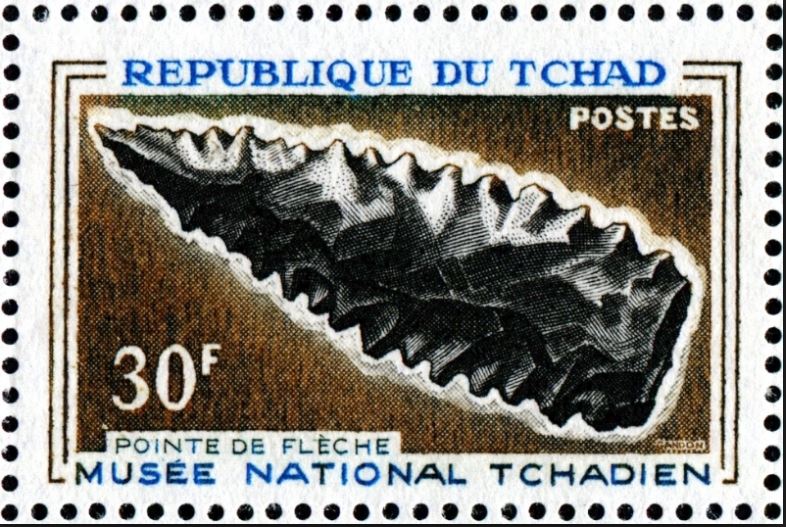

Flint arrowheads were used by hunters on all continents. Here is a 1966 postage stamp from Chad depicting such an artifact found there.References:

Genesee Valley Flint Knappers Association webpage

Long, D., 2004, A Workability Comparison of three Ontario Cherts, published in Kewa, the newsletter of the Ontario Archeological Society.