Fossil collectors will travel hours and brave cold temperatures and rain for a chance to collect trilobites. Heck, we will settle for trilobite parts. Most of us will pick up a complete brachiopod and even try to identify it by Genus. Check our garages and you will find hundreds, no thousands, of solitary rugose corals such as Heliophyllum halli and probably almost as many colonial tabulates such as Favosites or Pleurodictyum corals. We’ll jump for a gastropod and drool when a orthonic (straight-backed) cephalopod pops out in outcrop or shows himself (herself?) in a stone on the beach. And need I say more than Eurypterid to get you excited? BUT, who among us loves Bryozoans enough to even take a branching colony or a fan-like species home. And if you do take one home does it end up identified and in your collection? My guess is it does not. Perhaps I can change that.

Bryozoans are filter feeding sessile marine animals. They first appeared in the Early Ordovician Period and over 5000 species can still be found today, mostly in warm, shallow, marine water. In that sense they are not unlike corals. They too are not plants, although they are often called “moss animals”. Bryozoans feed and live like colonial corals and secrete a hard limy skeleton, but their living chambers do not contain septa and bryozoans have much more rudimentary and smaller tentacles than corals to deploy for filter feeding. You will often find bryozoan colonies encrusting other invertebrates.

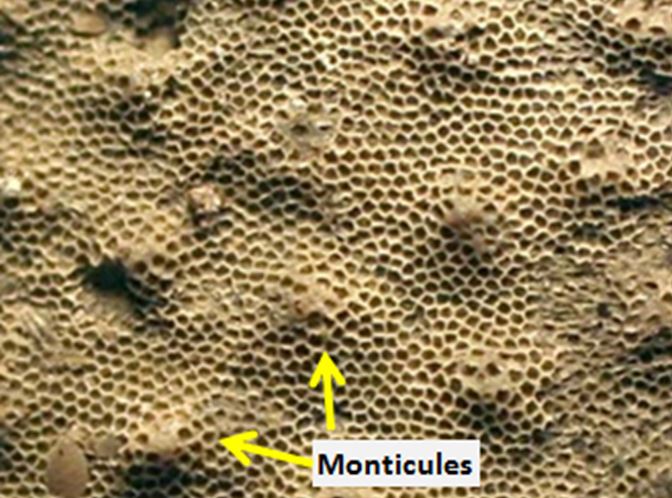

I was also guilty of generally neglecting this major phylum of invertebrates until last September’s trip to Cincinnati. The Ordovician bryozoans at two sites on that trip were “huge”; they could be measured in multiple centimeters and they had character! The individual chambers, called zooecium, where individual bryozoan organisms, called zooids, lived were visible to the eye. Upon inspection with a loop additional interesting character was evident. In addition to variability in their branching morphology, there were evenly spaced small bumps on some species, sometimes the raised regions seemed to be linear. Zooecium atop the bumps appeared a bit larger than others.

These bump-like features are called monticules. They are larger than the zooecium that cover both the monticules and the intervening depressions. For a long time, researchers were not certain about the purpose of the raised and often uniformally distributed monticules. They were just there and could be used to distinguish genus and species. But paleontologists studying bryozoans have an advantage that those working on trilobites or eurypterids or even dinosaurs do not have.

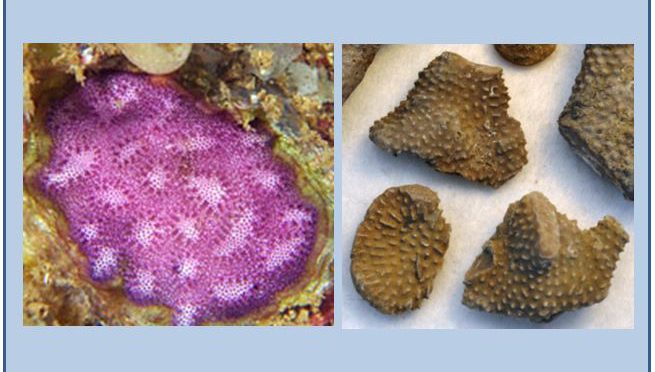

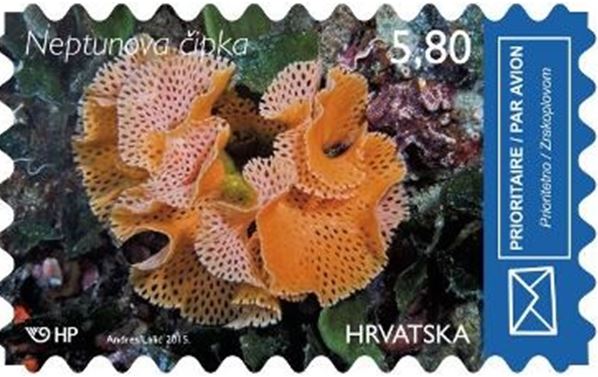

Bryozoans similar to the Paleozoic species we collect thrive today. The violet encrusting bryozoan in the left side of the cover photo is found in Hawaii. In fact, the country of Croatia featured Reteporella beaniana (Neptune’s lace) on a postage stamp in June 2015!

By studying modern bryozoans it has been surmised that the monticules or “chimneys” on the surfaces of many bryozoans facilitated water flow through the colony (Grunbaum, 1997). The integrated surface morphology such as that shown above improved the hydrodynamics that brought nutrient charged waters to the colony and discharged waste water back to the sea. Some zooids lived in the high rise portion of the colony while others settled in the valleys!

Identifying bryozoan genus is not easy. Perhaps that is why many of us typically refrain from filling our buckets with the darn things. But I believe I have been able to determine that I collected both branching Parvohallopra ramose and Monticulipora sp. (perhaps mammulata) in the Upper Ordovician at the Napoleon Quarry and at a roadcut in Vevay, Indiana (Hartshorn, et. al., 2016).

Now, back home in pseudo hibernation I am trying to rediscover the bryozoan I have collected in the Middle Devonian Hamilton Formation, the specimens I threw into the box because they were small or because I wasn’t finding much else that day. It is proving to be quite a challenge. Sometimes they are hard to distinguish from each other and I have little to report on that front yet.

There are over 20 species identified by Wilson (2014) in the Middle Devonian of New York alone and I probably have many of then hiding in my collection. They are classified by their size and morphology, their branching, fan-like or funnel shaped character and by the style of their zooecium and monticules. Often times they occur fossilized as epibonts encrusting other organisms, commonly corals and brachiopods, destroying or obscuring the features of the larger host. It will be a challenge to know what I have.

So, have I convinced you? Or will I be the only one paying attention to bryozoans this field season?

References:

Dry Dredger’s website: Bryozoa entry

Grὒnbaum, 1997, Hydromechanical mechanisms of colony organization and cost of defense in an encrusting bryozoans, Limnology and Oceanography, v 42(4),p. 7452.

Hartshorn, K.R., Kallmeyer, J.W., and Brett, C.E., 2016, Dry Dredging the Cincinnati Arch, Field Trip Guidebook for The Fossil Project, 40 p.

Wilson, K. A., 2014, Field Guide to the Devonian Fossils of New York, Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca, NY, 160 p.