Everyone likes the color purple and mineral collectors like shiny crystal surfaces and perfect terminations. Therefore, is it any wonder that amethyst attracts attention? Whether it is spotted in a 2” miniature specimen off matrix, filling a small geode, or covering a huge Brazilian crystal cathedral, eyes are always drawn to the splendor exhibited by a fine amethyst piece. Given its appeal, is it any surprise that amethyst is the February birthstone?

Quartz is hard, clear and common. Amethyst is hard, clear, not so common, and purple! One can enjoy amethyst without understanding the rather complex reason behind its color, but it is also interesting to know a little about the minerals in your collection. While complex in detail, it can be generally stated that it takes two very distinct properties to produce the distinct purple hue in amethyst. First, a small amount of iron must replace a few of the silicon atoms in the center of the SiO4 tetrahedrons upon which quartz is constructed. Second, the host rock must contain sufficient radioactive sources to emit gamma rays that over time irradiate the iron (Akhaven, 2012). This will cause the ferric iron (Fe+3) to jump to the unusual oxidation state of Fe+4. In this state it does not take much iron to impart a purple color and amethyst is born!

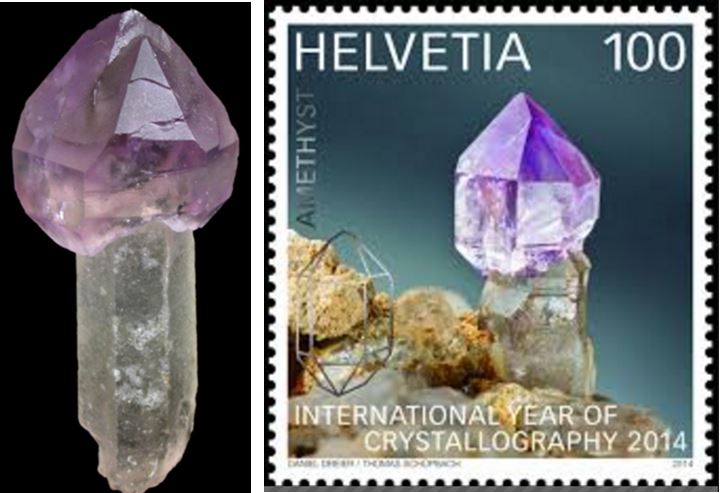

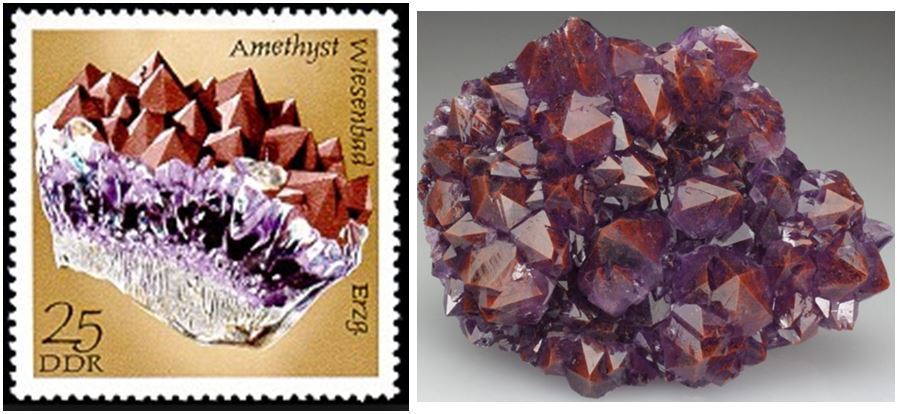

There are just about as many textural ways for amethyst to manifest itself as there are localities where it occurs. The very deep purple color of amethyst from Uruguay is probably due to the uniform distribution of iron and the strong presence of radioactive elements in the host basalt. In 1971, Uruguay featured their famous amethyst on a stamp (see above). Brazilian amethyst has a similar origin, hosted in fractures and vugs in basaltic lava flows, but can generally be distinguished by a slightly paler purple color.

Much of the world’s amethyst grows in fractures and vugs in volcanic rocks. These vugs can be regularly shaped geodes, or very large elongated “caverns” such as the famous Brazilian “amethyst cathedrals”.

Another prized form of natural amethyst is the specter. Quartz can grow in stages and sometimes smaller crystals are overgrown by larger ones. When the larger overgrowth is amethyst an exquisite piece is born.

Sometimes, there is so much iron incorporated into the quartz as it grows that the unradiated sample is red from microscopic hematite inclusions.

In recent years, WCGMC has collected amethyst in Prospect, Virginia and in Thunder Bay, Ontario. The Schuffin’s Acres Farm (previously Simpson Amethyst Mine) in Virginia exploits a mineralized fault zone where amethyst tips and clusters are recovered out of a weathering fault zone (Jacquot, 2014).

Amethyst is encountered in fractured and brecciated volcanics that covered the U.S.midcontinent region about 1.1 Billion years ago. The Amethyst Mine Panorama (a fee collecting site in Thunder Bay, Ontario reports a 60-70 year supply of amethyst, probably because Linda Schmidtgall got her supply at the Blue Point Mine in August 2013.

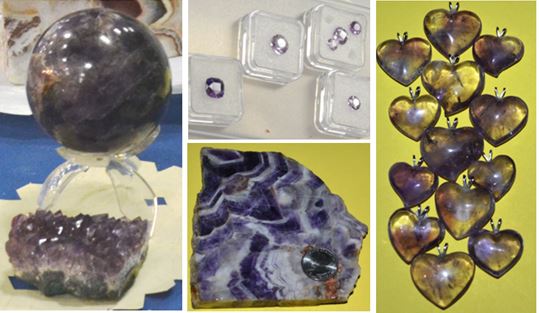

No discussion of amethyst is complete without reviewing its various lapidary uses and its quality as a gemstone. From simple polished stones, to banded cabochons, and, of course to faceted gemstones, amethyst is always finding its way into the project list of anyone working with stone.

References:

Akhaven, A. C., 2012, The Quartz Page: Amethyst, website: http://www.quartzpage.de/amethyst.html

Amethyst Mine Panorama website: http://www.amethystmine.com/

Jacquot, R., 2014, Scufflin Acres, Virginia’s Earth Shaking Amethyst, v. 1. #2, p. 55