Article I wrote in Nov. 2014 WCGMC News

Benson Mines, Rose Road (de ja vu all over again)

The leaves were changing (and even falling), but that did not deter a group of WCGMC folks from making a fourth trip to St. Lawrence County in late September. This time we were joined by 16 undergraduate geology majors from SUNY-Plattsburgh and their professor Dr. Mary Roden-Tice. It was truly wonderful to see so many young and eager folks enjoying geology and a day of collecting. The brilliant sun and the absence of mosquitoes did not hurt either.

Our first stop was the famous, closed Benson Mines iron ore open pit and dumps outside Star Lake, NY (see February, 2014 WCGMC newsletter). We were greeted cheerfully by caretaker George Peerson, and started with a quick stop at the crushed rock piles for a sampling of the granulite facies metamorphic gneiss rocks. Although the mining of iron ore ceased in 1978, the owners do sell the dump rocks as crushed aggregate. After a quick review of the interesting history of the location we drove the length of the open pit (now a gorgeous deep blue lake) to the huge ore piles that remain at the north end. Did you know the iron ore was discovered in 1810 by engineers surveying for a railroad when their compasses were wandering (Crump and Beutner, 1970)?

Everyone got to use their magnets and test their skills at distinguishing magnetite from martite, the later being the term for a hematite pseudomorph after magnetite. Crystal faces from the two iron oxide minerals show a slight variation in luster to an experienced eye, however we learned that the magnet is far more discriminating than our untrained eyes.

The sun was shining brightly as our caravan arrived at the north end of the pit and the large muscovite mica books in numerous pegmatite boulders were nearly blinding. In addition to the muscovite these pegmatites containe allanite, a rare-earth silicate mineral from the epidote group with the formula (Ce,Ca,Y)2(Al,Fe)3(SiO4)3(OH).

In addition to the allanite, small flakes of silvery molybdenite were speckled about in the quartz-rich pegmatite. We even found the foot long allanite crystal published in Lupulescu et. al.’s 2014 mineralogy article about Benson Mines (Figure 6). Don’t worry, it is still there for others to find, and if you do, please take only a picture. It is a classic.

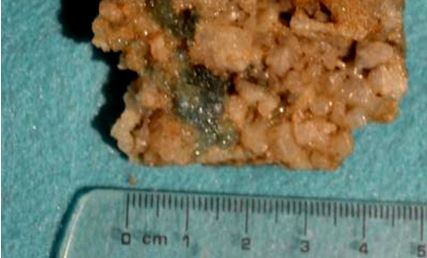

Less than 200m from the muscovite pegmatite occurrence was another large pegmatite boulder, but in this one the dominant aluminum-silicate mineral was sillimanite. Often the sillimanite at Benson Mines is altered to a yellow (sericite), green (chlorite) or stained red (hematite) (pers. comm. M. Lupulescu). But in this boulder the aluminum silicate mineral is deep green and almost gemmy (translation: very nice). With less quartz and more feldspar the assemblage there included two other neat silicate minerals, which were typically intergrown. Bright red almandine garnet (Fe3Al2(SiO4)3) was nicely set off by light green chrysoberyl (BeAl2O4). A few of these pieces even came with sillimanite.

The afternoon stop was about 20 miles east at the skarn bodies of Rose Road in Pitcairn. What a delightful place to take students interested in acquiring diverse minerals while learning metamorphic geology. The original site there is literally covered with green diopside, chocolate brown titanite, and white albite. It is not all crystalline and some that is cannot be easily extracted from the hard calc-silicate rock, but no one who visits this site goes home empty handed.

Although small the sky blue apatite set into the albite is pretty attractive as well. Even the wollastonite has a story to tell as it has been virtually completely replaced by fine yellow acicular diopside (Chamberlain and Robinson, 2013). Unlike the coarse green diopside, this replacement diopside is too fine to see even with a hand lens, but perhaps an industrious student will cut a thin section and test it out back in Plattsburgh. As with martite at Benson Mines, these specimen illustrate the concept of a pseudomorph as the triclinic crystal structure of wollastonite is preserved.

Less than 200m from the wollastonite-diopside ridge is a second occurrence of calc-silicate mineralogy with a very different mineral suite. Discovered only in 2011, the dominant skarn minerals at this second location are scapolite (variety meionite, S. Chamberlain, pers. comm..), a lavender diopside, fine gemmy phlogopite, titanite, apatite, and a course tan calcite. The scapolite fluoresces bright canary yellow and some excellent crystals up to 8 cm have been recovered from fracture surfaces. It would be indeed interesting to study how these two mineralized regions relate to each other. Unfortunately the region between is heavily forested and outcrop exposure is sparse.

When listed out in their entirety, the complete suite of minerals available from the two sites visited is rather impressive. We even made a quick stop at the satellite tower at the top of Rose Hill. The pad there is built with marble aggregate from the Balmat mine and it is laced with red—brown sphalerite and pyrite. Two more minerals for the student’s growing collection and from yet another of upstate New York’s world class ore deposits.

References:

Chamberlain, S.C., and Robinson, G.W., 2013, The Collector’s Guide to the Minerals of New York State, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., pgs. 46-49.

Crump, M.R., and Beutner, E.I., 1970, The Benson Mines Ore Deposit, St. Lawrence Co., NY, in Ore Deposits of the United States vol. 1, pg. 49-71, ed., J. D. Ridge, American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineering, Inc.

Lupulescu, M. V., 2014, The Benson Mines, St. Lawrence County, NY, Rocks & Minerals, # 89, 118-131.