Lots of folks like minerals. Many of us also like to cook. At the October meeting of the Wayne County Gem and Mineral Club Inga Wells brought native bismuth and her “cooking” equipment and showed us how to cook up some bismuth crystals. Everybody got a close-up look at bismuth stew and then got to take a piece home.

Bismuth (Bi) is a post-transition metal with an atomic number of 83, directly beside lead on the periodic table and below antimony and arsenic. However, unlike arsenic, bismuth is non-toxic and heating to the melting point does not emit dangerous fumes. That said, the silvery-white metal melts at 530⁰ F so you might want to wear gloves and observers should keep at a distance while the crystals grow. Inga told us that stainless steel pots and silverware and a hot plate seem to be the best tools for heating and handling the molten material. It is further recommended that once pots are used with bismuth that they are retired from primary kitchen use! You can also see that Inga wore safety goggles, although not gloves.

Some comments from Inga while she demonstrated heating, cooling and extracting crystals.

“The best part of working with bismuth is that you can re-melt crystals that you do not like. It is different every time you do it due to room temperature and how fast oxidation happens”

“I like doing it outside on a hot summer day. The slower the crystals cool, the better they seem to be. Once the melted bismuth starts to cool, you need to pay close attention. This is not a good project for multi-tasking.”

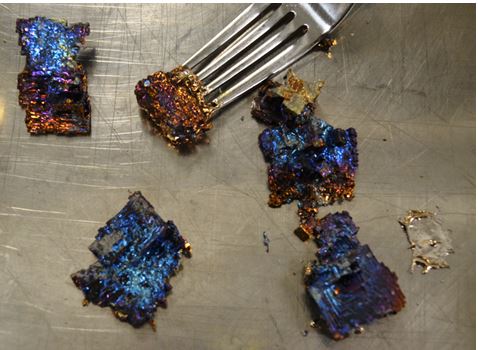

“You can knock the cooled crystals off of tools and pry the crystals apart with pliers, or cut with a saw”.

Native bismuth is rare and seldom present in significant amounts. Despite being rare, bismuth was one of the first ten metals discovered, and it held a prominent position in Group V of Dmitri Mendeleev’s first Periodic Table 150 years ago (May 2019 WCGMC newsletter). Most bismuth is recovered as a by-product of mining other metals like lead. The metal is seldom used as pure bismuth but rather as an oxide in pharmaceuticals and chemicals or as an alloy in steel. Because bismuth is inert and non-toxic it is finding new applications as a replacement for lead in plumbing, soldering, and other applications. Unfortunately, this replacement comes at a cost.

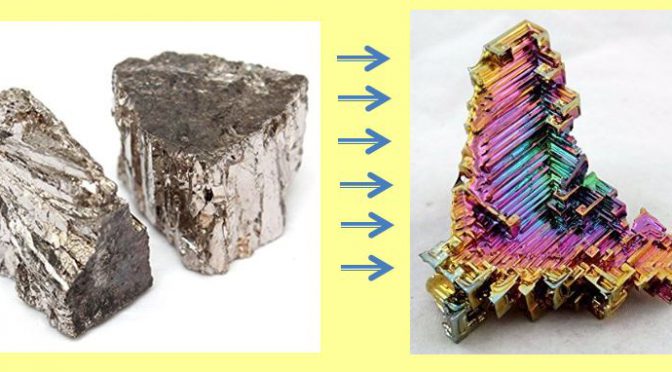

For those with aspirations of growing beautiful bismuth crystals, chunks of native bismuth (such as those on the left in the header photo) can be purchased online from many suppliers at about $15/pound. Inga did note that melting 3-5 pounds of bismuth seems to be best for growing large and intricate crystal forms, but remember the material that is not part of the crystal itself can be re-used.

Some of Inga’s creations: the brilliant color and iridescence of synthetic bismuth crystals are produced by the interference of light within a thin oxide film that forms on the metallic surface when the crystals grow. With practice and more ideal conditions, crystals like that on the right in the header photo can be created in the “kitchen”.