In August, the Wayne County Gem and Mineral Club undertook a two-week trip to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The trip took us through Marquette, or more specifically the Marquette Iron District, where we spent three nights visiting and collecting. We attended two field trips planned by the Ishpeming Mineral Club, their club show, and also made several trips to Presque Isle Park and other Lake Superior shoreline locations. It was on the first of the club trips that we were introduced to the Iron District and to taconite. We visited the enormous dumps of the Republic Iron Mine, 20 miles west of Marquette.

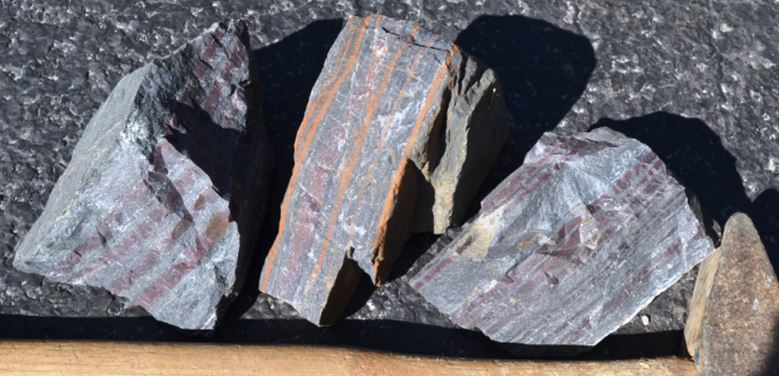

Taconite is the term used for the low-grade iron ore found in many Precambrian sedimentary sequences around the world. These unique rocks tell an interesting geologic story and are equally important economically. Geologists refer to the rocks miners call taconite as “banded iron formation” (or BIFs). They are composed of alternating bands of magnetite (or sometimes hematite), chert/jasper, and/iron silicates (cummingtonite/grunerite). The magnetite is black, the jasper various shades of red, sometimes the silicate layers are green. Together they can create colorful rocks that are prized for landscape use, for lapidary work, and just simply for their unique beauty. These bands can be monotonously repeated or they can be highly variable in thickness and content. Often the bands have been intricately folded during tectonic activity and interesting metamorphic minerals can form. Note the folds in the “Banded Ironstone” pictured on the 1982 Zambia postage stamp to the left.

The term taconite was coined by Horace Winchell, State Geologist of Minnesota. He was mapping the Precambrian Iron Formations of northeastern Minnesota in the early 20th century and he noted that the rocks resembled the iron-bearing rocks from the Taconic Mountains of New York, his home state.

Rock collectors may cherish the red/black banding of jasper and magnetite, however, the presence of all that jasper together with the iron oxide ore minerals posed a problem for early miners. Until the mid-1900’s relatively pure iron ore (either red hematite or black magnetite) could be successfully mined that carried 50-60% iron content. The rocks in BIF typically contain 20-30% iron and it was (and still is) uneconomic to ship ore of that grade to steel mills (Mategko, 2011). But in the 1950’s an engineering breakthrough allowed for the economic processing of these low-grade ores. Taconite became the ore of choice for many steel mills.

The first part of the problem was not complex. The ores were ground to a powder and the magnetite separated from the siliceous material with magnets. But the powdery black product was not conducive to long-distance transport. University of Minnesota professor and researcher E. W. Davis literally conducted two decades of experiments concocting an economic method to process and transport the enriched iron ore. The process involves mixing the magnetite with bentonite clay in large rotating cylinders causing the concentrate to form into balls much like wet snow. These are passed through rollers spaced about a centimeter apart to ensure a consistent size to the pellets. Note the dime inside the c of taconite pellets in the title of this article.page.

The taconite pellets generated from this process are perfectly designed for what follows. First, they are easy to load on railroad cars and then large Great Lake barges using conveyor belts and rollers. But, perhaps more importantly, when they are “rolled” into the blast furnaces at the steel mill the increased surface area provided by the pellets optimizes the process of melting and recovery of iron (Breneman, 2018). In locations like Marquette where limestone is readily available, the optimal amount of limestone can be added during pellet formation and the steel mill need only load the taconite pellets and turn on the furnace. Limestone is used as a flux, acting to grab silica dioxide and other impurities in the melted iron ore. This waste material floats to the surface and is removed. We call this slag and it is commonly found around iron foundries of any age or style. The Marquette beaches are rich in this material where it is locally referred to as “Lake Superior beach slag”. And yes, we collected some of that, but that is another story!

In addition to collecting quartz and magnetite mineral specimens and banded taconite ores at the Republic Mine, we decided we could not come home without some bonafide taconite pellets. We found that to be very easy. The railroad line that runs from the active iron mines in Ishpeming and Negaunee to the port in Marquette is literally covered in the marble-like magnetic pellets that had fallen off during transport. All we had to do was stop and pick them up. It is a sure bet you will see some soon in some WCGMC activity, perhaps we’ll play marbles with them, or see how many can be moved from one pile to another with a small magnet in one minute.

References:

Breneman, J., 2018, “How Innovation Saved the Iron Range”, Univ. Minn. Duluth Natural Resources Research Institute.

Mategko, S., 2011, Iron Range 101: What is taconite?, Twin Cities Daily Planet, 9/18/2011

Mindat webpage, “Definition of Taconite Pellets”

Wikipedia Entries for “Marquette Iron District” and “Taconite”