It seems we have been here before! The May gemstone is a repeat of the mineral beryl. Yes, emeralds are a different color than the March gemstone aquamarine, but mineralogically a beryl is a beryl is a beryl.

The striking green color of an emerald is caused by the introduction of just 0.1-0-5 percent chromium substituting into the aluminum spot of the beryllium silicate mineral. A small amount of vanadium is also present. It is truly amazing that just a fraction of a percentage of an element can impart such a striking difference in color. While the richness and intensity in color is paramount in valuing an emerald, the presence of visible inclusions is also important. Emeralds lacking inclusions to the eye are considered flawless and carry more value than those with visible inclusions.

The striking green color of an emerald is caused by the introduction of just 0.1-0-5 percent chromium substituting into the aluminum spot of the beryllium silicate mineral. A small amount of vanadium is also present. It is truly amazing that just a fraction of a percentage of an element can impart such a striking difference in color. While the richness and intensity in color is paramount in valuing an emerald, the presence of visible inclusions is also important. Emeralds lacking inclusions to the eye are considered flawless and carry more value than those with visible inclusions.

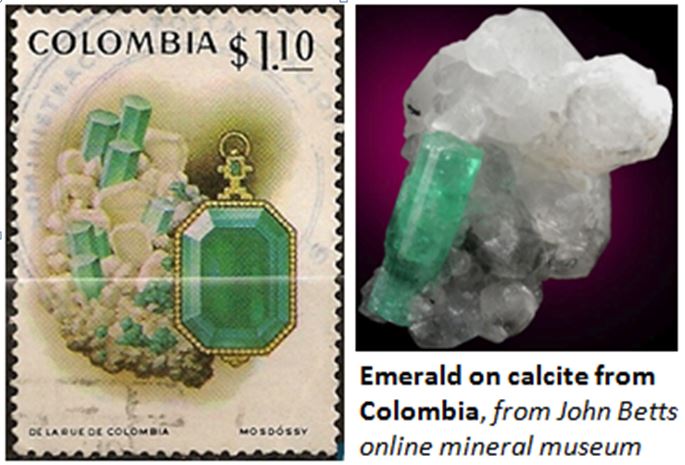

More than 60% of the world’s best emeralds continue to come from the remote jungle regions of Columbia. They have formed in thin seams in Cretaceous age carbonaceous shale and limestone that were invaded by hot beryllium-rich fluids moving along fault zones adjacent to the sedimentary units. When these fluids cooled the beryl was deposited, often associated with calcite which can be etched away. The igneous source rock for the hot hydrothermal fluids has not been located. It may remain buried or its surface exposure may be hidden by jungle soil and vegetation. The chrome is thought to be sourced from the black shales, while the beryllium is delivered by the hydrothermal solutions. The reducing environment of the shales then promotes emerald formation.

With a hardness of 7.5-8, emeralds can survive to weather out of shale and be recovered in nearby placer deposits or in tailings just outside the mine. But emeralds tend to fracture during transport so most must be mined at their source in underground workings, many of which are dangerous and poorly supported. Given that the host rock is estimated to contain only about 1 carat per every 15 cubic meters of rock, it is very hard work.

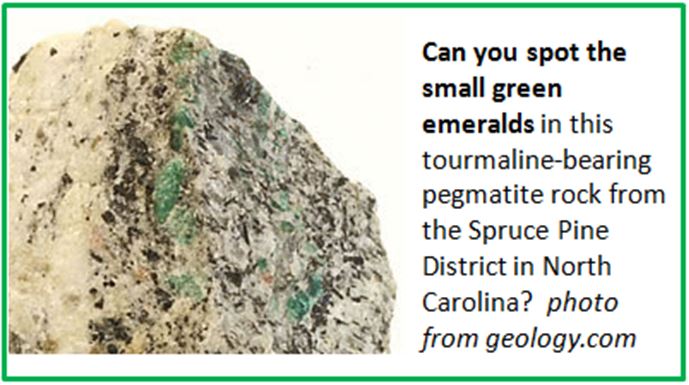

Emeralds also occur in mica schists and in pegmatites. Perhaps the most famous eastern United States occurrence is in a few small pegmatites in North Carolina.

For more on the mineral behind the emerald, here is a link to the March 2016 WCGMC newsletter.

References:

Lauf, R.J., 2011, Collector’s Guide to the Beryl Group, Schiffer Earth Science Monographs, Volume 11, 93 p.