co-authored with Stephen Mayer for the March 2016 Wayne County Gem and Mineral Club newsletter

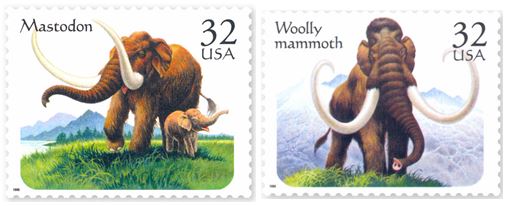

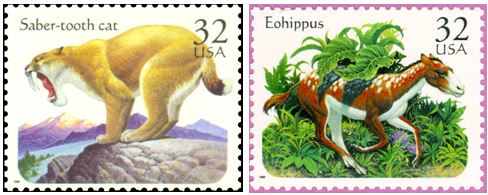

As geologists and amateur fossil and rock hounds, many of us focus on the Proterozoic minerals of the Adirondacks and/or the Paleozoic fossils of western and central New York State. However, two very important and much overlooked prehistoric animals roamed New York State approximately 10,000 years ago. The Woolly Mammoth and the American Mastodon were prominent residents in our own backyards.

In fact, one of the more famous and complete Mastodon skeletons unearthed in New York State was found on the Pirrello celery farm just seven miles north of Newark in 1973. The bones were uncovered about 75 cm below the surface in a gray marl layer. What’s more, the founders of the Wayne County Gem and Mineral Club, Jim and Marion Wheaton, were instrumental in the historic discovery and the resulting dig. Over 40 vertebrae and foot bones were recovered and radiocarbon dating indicated that the Pirrello Mastodon had died approximately 11,700 years ago (Ference and Kozlowski, 2012). Marion Wheaton’s summary of the event makes for interesting reading in the July 2008 issue of the WCGMC News (linked here).

Discovered a few miles west, a molar of a Woolly Mammoth excavated during the 1910 construction of the NYS Barge Canal Lock 26 just 2.5 miles east of Clyde has been dated to about 11,750 BP (9800 BC). Such close radiocarbon dates and proximity of where the remains were found provide evidence for the coexistence of Mastodons and Woolly Mammoths in New York State during the waning stages of the last Ice Age.

So, how do scientists distinguish Mastodons from Woolly Mammoths? And what do these differences tell us about their relative size, their preferred environments, and their diets?

The Woolly Mammoth was first described by Georges Cuvier in 1796 as an extinct species closely related to the extant Asian elephant. The appearance and life history is well known from the discovery of not only fossilized bones but also frozen carcasses from Siberia and Alaska. The males grew to 9-11 ft at the shoulders and weighed approximately 6.6 tons whereas females grew to 8.5-9.5 ft in height and weighed 4.4 tons. The mammoth was well adapted to the cold environment of the last Ice Age having a heavy woolly outer coat of fur, which reached lengths of 35 inches on the flanks and underside and an under coat of dense curly wool 3 inches thick. Moreover, the ears and tail were short to minimize frostbite and heat loss.

The Woolly Mammoth had very long, curved tusks (modified incisor teeth), which in males typically reached 7.9-8.9 ft long and weighed 100 lbs. Females tusks were shorter and thinner averaging 4.9-5.9 ft long and weighed only 20 lbs. They had 4 molars with 26 ridges of enamel and were replaced 6 times during a lifetime.

The Woolly Mammoth’s trunk was large and muscular and together with the tusks was used for foraging and drinking water, displays of territorial and intra-species dominance as well as defense against predators. Furthermore, the molars were particularly useful in grinding mainly grasses and sedges. An adult may have lived 60 years when its last set of molars had worn out and the animal died of starvation.

The Mastodon was similar in appearance to modern elephants and to a lesser extent to the Woolly Mammoth but not closely related to either. Although fossil bones have been found in Asia, they were widely distributed throughout North America from Alaska to Florida, and from California to New York. The Mastodon had shorter legs, a longer body and was more heavily muscled than Mammoths. The average size of a large female or small male was 7 ft 7 inches in height at the shoulders whereas large males ranged from 9.5 ft – 13.5 ft tall and weighed 15-18 tons. Unlike the Mammoth, the head was low and long, not high and domed. The tusks were strongly curved especially in the males. Furthermore, Mastodons had cusp-shaped teeth in contrast to the enamel plates of Woolly Mammoth and elephant teeth. They were well adapted for mastication of leaves and branches while browsing in forests.

Although Mastodon bones were discovered in the early 1700’s, the species was not recognized until 1817 by George Cuvier noting the conical shaped teeth as belonging to a different species other than Mammoth or elephant. As a genus, Mammut (Mastodon) diverged approximately 27 million years ago from Mammoths and elephants.

The Woolly Mammoth and the American Mastodon both disappeared about 10-11,000 years ago during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene along with other Pleistocene megafauna possibly either due to overhunting by Clovis Indians, climate change or both. A few isolated populations of Mammoths survived up to 4300 years BP on Wrangel Island in the Arctic of northern Canada and their disappearance coincided with the appearance of human arrival. Still further warming of the climate contributed to significant loss of habitat placing additional stresses on populations until neither species could no longer survive.

Unlike collecting trilobites and tourmalines, fossil hunters cannot explore one locality and expect to discover excellent Woolly Mammoth or Mastodon bones. Quite to the contrary, almost all partial and nearly complete specimens have been found by accident over many years scattered across the land. Maybe the WCGMC can be lucky and make such a fortuitous discovery on one of its adventures this summer.

References:

Feranec, R. and Kozlowski, A., 2012. New AMS Radiocarbon Dates from Late Pleistocene Mastodons and Mammoths in New York State, USA. Radiocarbon, Vol. 54, No. 2, p 275-279.

Paleoaerie.org, 2014, Fossil Friday, a fossil of not qute mammoth proportions, Arkansas Education Resource Initiative website

En.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woolly Mammoth, 2016

En.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mastodon, 2016

NYSM.nysed.ogv/exhibits/longterm/mastodon