There are many well known fossil collecting sites in the creeks and gullies draining into the Finger Lakes (places like Kashong Gully, Deep Run, and Portland Point to name a few). But for every well documented site there are a dozen lesser known locales where drainages into the Finger Lakes expose the fossil rich strata of the 385 million year old Middle Devonian Hamilton Group. Indian Creek, near Williard on the eastern side of Seneca Lake, is one such location.

Upon entering Indian creek off of East Lake Road just north of the hamlet of Willard, one immediately encounters a unit with large irregular concretions exposed in the bedrock. To an untrained eye some might even be confused with dinosaur bones. One land owner that Stephen Mayer and I visited during an October excursion was absolutely convinced of this and had even built a nice wooden stand to hold his prize “bone”.

Given that the Menteth limestone is exposed at the lakefront in this region, one would suspect that these concretions and the entire stratigraphic section in Indian Creek would expose the overlying Kashong and Windom Shale members of the Moscow Formation. However, it is not that simple. There is apparently some faulting in the area which may lead to repeat section in the creek bed. Jacobi (2002) mapped major cross-faults in the creek and Luther’s 1907 Seneca Lake bedrock geology map shows older rock than Menteth extending up Indian Creek.

Even armed with all this wonderful input, Stephen and I could not convince ourselves that we were not in a straight forward Kashong shale section as we waded upstream. Perhaps it was all the fallen leaves that covered the pertinent geology, but more than likely our failure was that we had our eyes glued to the shales looking for fossils. While we did not get leave with a comfortable understanding of the stratigraphy we did leave with some fossils.

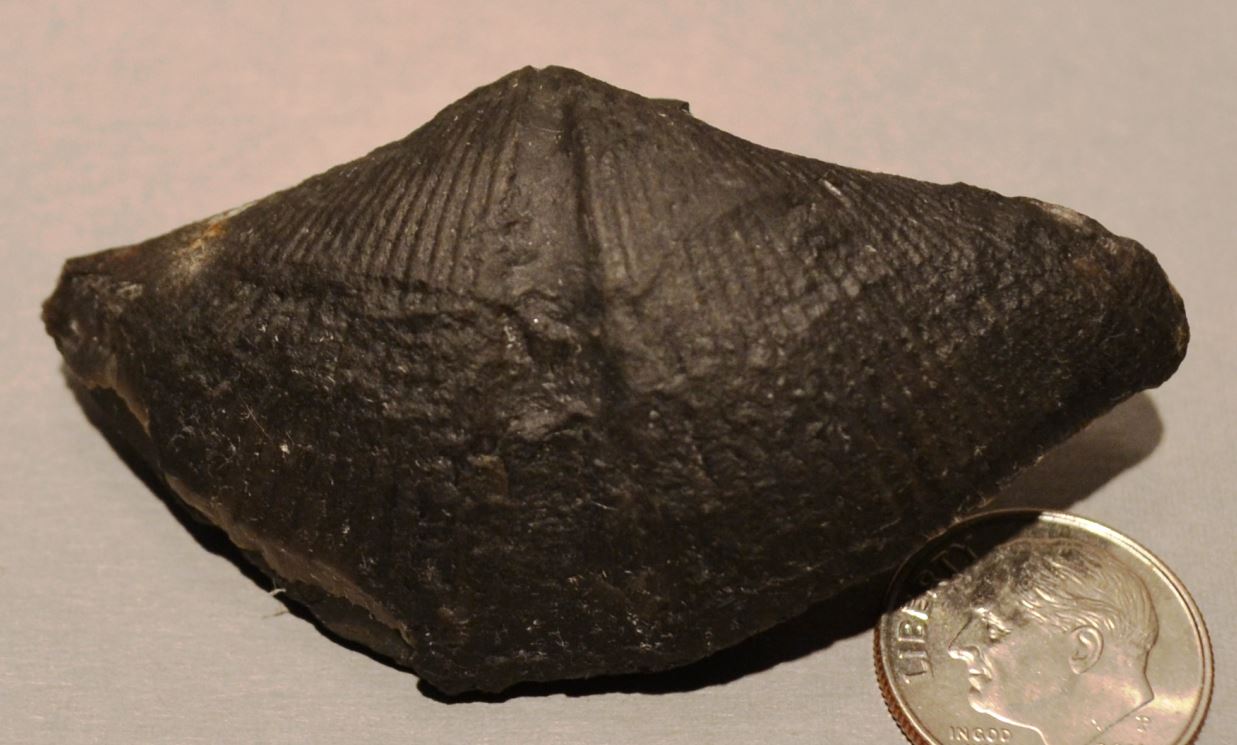

About 1500’ from Lake Road and at a major fork in the creek we encountered our first bona fide fossil bed. Multiple species of brachiopods including Spinocyrtia granulosa, Mucrospirifer mucronatus, Rhipidomella sp., and the ubiquitous Tropidoleptus carinatus were waiting to be collected, but my day was made finding three perfectly symmetric and complete Pleurodictyum americanum. You may recall from an earlier note that “pleuros” are my favorite fossil and this was a new locality for me to boot.

Another interesting aspect of Pleurodictyum coral is that they appear to require a hard substrate on which to grow. Some grow on rocks, others on carbonate hardgrounds, but the most common substrate seems to be another fossil (Brett and Cottrell, 1982).

Indian Creek splits into two major creeks about 1500’ from the lake. We walked each fork a short distance, but had spent our energy for the day collecting fossils near the confluence. We will need to return next year and walk up each to find ourselves stratigraphically. Perhaps we can find the phosphatic pebble bed at the top of the Kashong member near the base of the Windom. Morevover, maybe we will traverse the entire Windom and find the Tully limestone that caps the Moscow Formation. This could establish where we were collecting. Until then, knowing that we were in the Kashong shale member will have to suffice.

References:

Brett, C. E. and Cottrell, J. F., 1982, Substrate specificity in the Devonian tabulate coral Pleurodictyum, Lethais, V. 15, p. 247-262

Haynes, F. M., 2014 Pleurodictyum americanum, WCGMC News, Nov. 2014, p 2-3.

Jacobi, R.D., 2002, Basement Faults and seismicity in the Appalachian Basin of New York State, Tectonophysics, V. 53, p. 75-113.

Luther, D.D., 1907, Geology of the Geneva-Ovid Quadrangles, NYSM Bulletin 128.

=================================================

Indian Creek does not appear to be posted, but as with all creeks and off road regions along the Finger Lakes permission to enter should be sought before entering.