In mid-October, over 130 mineral collectors from several northeast states and Canada converged on Walworth Quarry in upstate New York for the annual fluorite hunt. Every May, the same crowd treks to Penfield, NY when The Dolomite Group opens that quarry to folks hoping to score a nice transparent-purple fluorite or maybe some dogtooth calcite. Closer to Buffalo the prized finds are dogtooth calcite, clear selenite, and, of course, small purple fluorites when clubs visit the Lockport Quarry.

Granted the fluorite and other less common vug filling minerals like sphalerite, celestine, and honey colored dogtooth calcite are nice finds and worthy of special attention. But, there is another fine crystalline mineral hiding in the vugs of the Lockport dolostone. Yes, I speak of the carbonate mineral, dolomite, or CaMg(CO3)2 Everyone shines their flashlight into the dark vugs of car-sized boulders hoping to see a flat transparent cubic cornered, multi-inch fluorite gleaming back at them. Absent that observation, collectors move on to the next vug, the next boulder, the next quarry face.

In the next few paragraphs, I am going to try to convince you to take a second look into the vug. Pause a few seconds to evaluate the white to pink dolomite crystals that you are categorically dismissing as unworthy of your collecting attention. Are not most of the vugs lined with clean shiny dolomite crystals? Is there a floater piece in the vug that can be easily removed that displays multiple tiers of brilliantly terminated rhombohedral dolomite? If yes, just why are these not worthy of extraction?

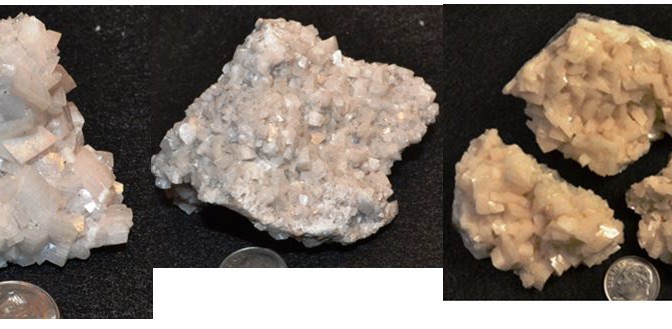

We will start with Walworth, the most recent location where many of us turned over and pounded on rocks. Most of the dolomite there is white. Crystals line the vugs and often vugs are so closely spaced that small dolostone remnants can be caught between vugs with both sides coated with dolomite crystals. The individual crystals are typically less than 1 cm in size, but can be a bit larger. The aesthetics of any given piece depend on the organization and display of the crystals atop the dolostone matrix, and, as always, on the eyes of the beholder.

In my limited experiences (two visits), Penfield Quarry dolomites are typically smaller than those at Walworth, but they are just as brilliantly white and can coat and fill vugs completely. It is great when a mat of the small white dolomite crystals provide the base for one inch or larger fine dogtooth calcites, but they can be fine without any mineral cover also.

The dolomite from Lockport Quarry close to Buffalo is easily distinguished from that of the other two quarries. It is noticeably pink. The pink color generally reflects minor iron substituting for magnesium position in the dolomite lattice. Dolomite is trigonal, and like calcite, has three cleavages, that form rhombohedrons.

In my observations, the Lockport dolomite is the best location of the three for observing curved or twisted rhomobohedral dolomite crystals. Dolomite crystals that are not perfectly rhomobohedral are often called saddle dolomite. They are characterized by curved crystal faces which impart almost a warped appearance. Although the origin is poorly understood, most saddle dolomites show Ca-enrichment towards the crystal edges. It has been theorized that rapid growth leads to the development of extra wedges of growth at crystal edges causing the curved appearance (Searl, 1989).

Most of the occurrences of dolomite in western New York (and there are many more than the three I mention here), are hosted by the Lockport Formation of Middle Silurian age (~420 million years). The unit averages 200 feet thick and outcrops in an east-west swath of some 200 miles from Niagara County in the west to Herkimer County in the east. The trend continues west into southern Canada and there are numerous Silurian dolostone quarries there as well.

The unit is very resistant and is a prominent ridge former in western New York. The Lockport dolostone forms the lip of Niagara Falls and the Upper Falls of the Genesee River in Rochester. It is this resistance and hardness that makes it useful in construction applications and as crushed stone for landfill and landscaping.

The original rocks formed in a tidal environment when New York was much closer to the equator. Periodic exposure of the limey muds and recently lithified limestone and dolostone permitted ground water to penetrate the upper intervals forming vugs and cavities by dissolution. When the rocks were later buried as deeply as three miles hot brines (150-170ºC) found their way to the vugs and precipitated the remarkable set of minerals we find today. As the host dolostone is predominately comprised of the mineral dolomite it is not surprising that dolomite also dominates the vug filling.

Much of the surface exposure and vug generation occurred near the end of Lockport deposition so the mineralized layers are generally restricted to the uppermost layers. Collectors are wise to ask where the operators have moved the upper faces back recently when they visit. The deeper levels provide great dolostone for industrial use, but carry little of interest to collectors.

OK, so have I convinced you to collect a little dolomite on your next quarry trip?

References:

Amos, F. The Rocks of Western New York, RAS online site

NYSM Webpage: Minerals of New York’s Lockport Formation,

Searl, A., 1989, Saddle Dolomite: a new view of its nature and origin, Mineralogical Magazine, v. 53, p. 547-555.