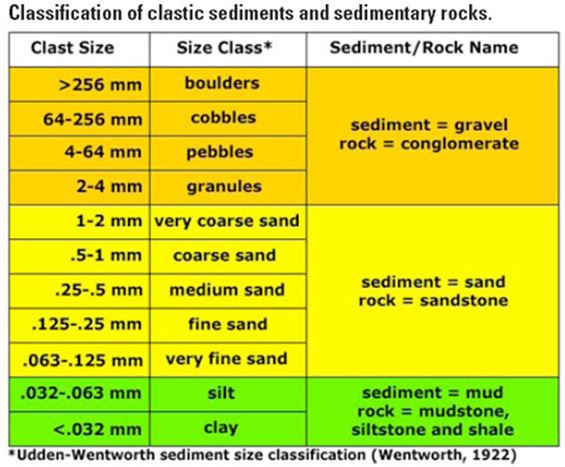

This month I was working with “sand” that was actually too large to be technically called sand. Rather the grains were granules, the finest size fraction of gravel. I had obtained 200ml samples of four different gravels from Ed Tindell, a Texas collector, trading him gravels from northeast locations I had visited. One of my new samples was from Sunstone Knoll in Millard County, Utah. The gravel had accumulated in the alluvium shed from adjacent Sunstone Knoll. Ed had size-sieved a large sample and the material he sent me was from the 1/16” to 1/8” (1.7-3.2mm) size range, bridging the upper limit of sand, but mostly fine gravel or granules (see chart at the end of the article).

There are three primary materials in the gravel. The largest amount (over 60%) is andesite. The volcanic vent that formed the small knoll erupted 1.6 million years ago leaving a vent of andesitic to basaltic lava which is gradually eroding. Two other grains are present in appreciable amounts, a lighter colored grain that is altered breccia and a brilliant transparent grain, which is the sunstone for which the location is named.

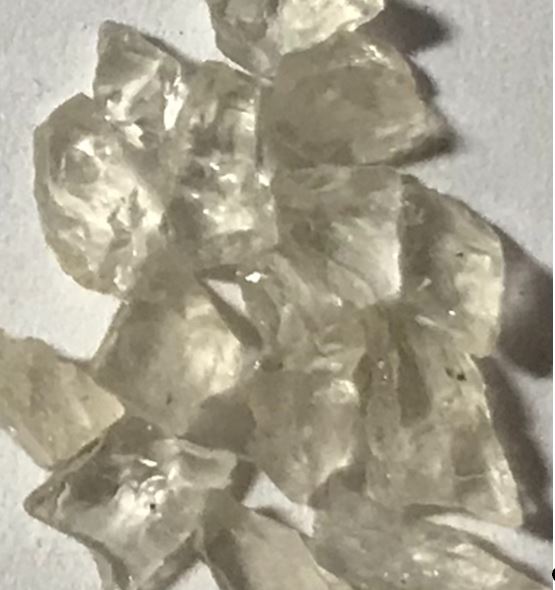

The sunstone grains are highly reflective and glitter under sunlight or bright light. The clear, pale yellow mineral is labradorite (a calcium-rich form of plagioclase) that forms in cavities in the lava. Larger pieces can be obtained by splitting open the andesite (a bit like Herkimer hunting I guess). However, the flats surrounding Sunstone Knoll are littered with small glittering grains that have been eroded from the central feature. The granules Ed sent me contain about 15% labradorite (sunstone). As the individual grains get smaller they appear clearer with less yellow color, but the clear grains sure sparkle under any form of light.

Ed Tindell administers a Facebook page called “Gravel Sorting Adventures”. He likes to sort large amounts of gravel from locations with diverse mineral and rock types, separate the grains, and then count/weigh the individual components. Of course, this gets harder as the size fraction you select gets smaller. It seems gravel is more amenable to this hobby than sand. Right now I think I prefer to leave the sand or gravel I sample intact, but the idea does have some appeal.

References:

Introduction to Geology, Chapter 9 – Sedimentary Rocks and Processes, a free online textbook of geology

Tindell, E., 2019, Frozen Beer, select Gravel Sorting_Rev8.ppt from the this list on Gravel Sorting Adventures

Wentworth, C. K., 1922, A Scale of Grade and Class Terms for Clastic Sediments, The Journal of Geology, volume 30, no. 5, p. 377-392.

Wilkerson, C. M., The Rockhounder: Sunstones at Sunstone Knoll, Millard County