Almost anywhere we wander in New York, we are apt to encounter glacial erratics, rocks that were transported to their current locations by the great sheets of ice that covered the state as recently as 10,000 years ago. Typically we just step over, or walk around, these aberrant rocks. That is, unless we trip on them, in which case we curse their existence before we move on. Farmers detest them too, but will use them to build stone walls or cobblestone barns. Once in a while we might notice something interesting in them and stop to smack them with our hammers or mauls. Typically they resist such actions, providing us a reason to detest them even more.

But there are some really famous glacial erratic boulders in the world. Some are famous for their size, others for their location. Perhaps you have a favorite one? I’ve selected a few to highlight.

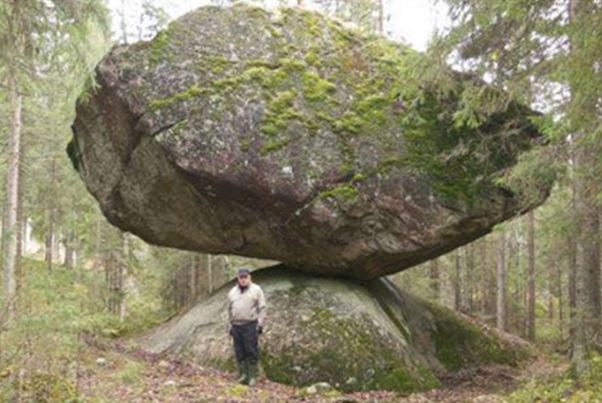

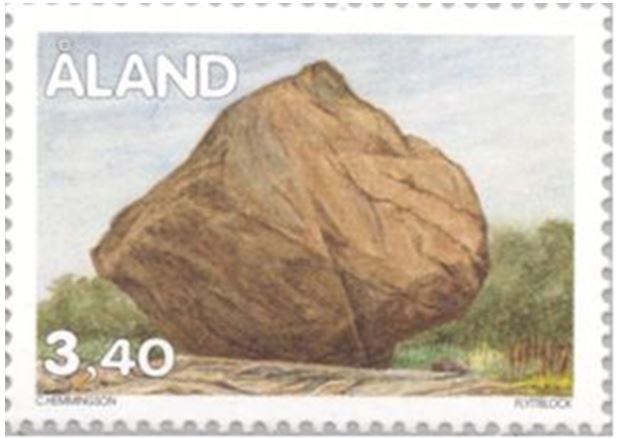

Kummakivi is 7m long but due to the concave shape of a small part of its base it is able to sit almost miraculously on another rock. There is less than a square meter of contact between them. The lower boulder is an erratic itself with only a small portion exposed. You can imagine the ancient folklore that evolved to explain this formation. It involved giants and trolls who liked to throw rocks about and, on occasion, build large cairns and balance rocks.

Has anyone climbed Bald Mountain and marveled at how a glacier could have dropped that off there while retreating? Bald Mountain is 2350’ high and the hike to the summit is 1.9 miles long. In addition to this erratic and the granite gneiss outcrops, the climb terminates at one of the best known and most picturesque fire towers in the Adirondacks.

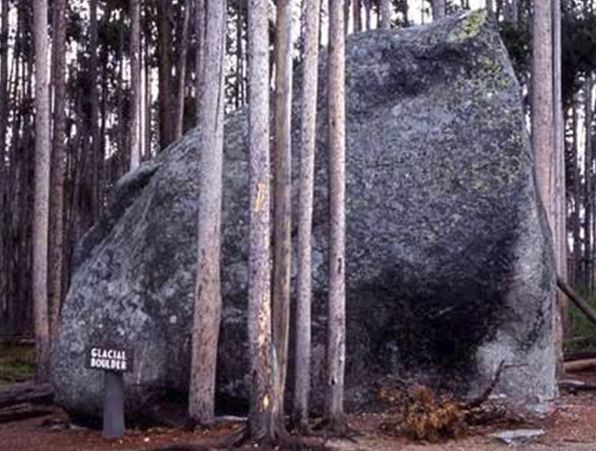

The Madison granite boulder is 83 feet long, 37 feet front to back, 23 feet tall, and is estimated to weigh 6000 tons. It is purported to be the largest glacial erratic in New England, although I am not certain that is an official title. Although clearly an erratic there is controversy about its source. Most trace the boulder to the Conway Granite of Mount Whitton about 4 miles northwest, but some maintain that the granitic composition better matches Mount Willard in Crawford Notch about 24 miles northwest. Regardless, the immense rock is now designated as a National Natural Landmark and is available for all to see, walk around, and climb in the Madison Boulder Nature Area.

Did you notice anything similar among all these large rocks? Look carefully. They all show some development of lichen on their surfaces. Some show cracks. All were placed at their current resting places at the end of the last glacial period some 10,000 years ago. And weathering has started. The lichen, in combination with rain, freeze/thaw and probably some human action, is starting to break them up. Eventually, they will be eroded to smaller and smaller rocks, and then sand that will be carried away. Geology is never stagnant. It can be slow, but it is relentless and continual. These rocks don’t have a chance. Eventually, they may become part of someone’s sand collection.

References:

Atlas Obscura webpage, Kummakivi Balancing Rock, Ruokolahti, Finland

Martin, C., et. al., 2004. NH Has Got Stones, New Hampshire Public Radio webpage

Sweeny, J., 2019, Wikipedia Commons