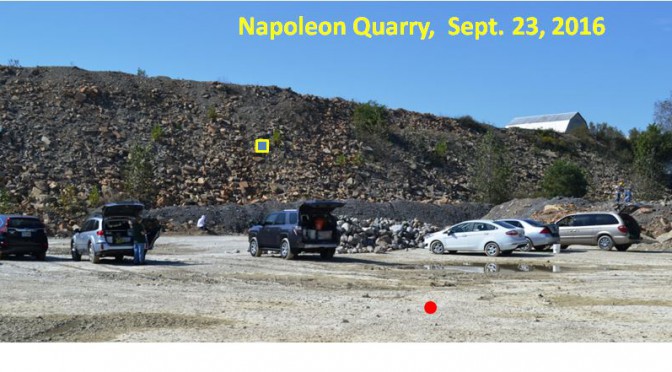

In mid-September, Bill Lesniak and I ventured a couple states west and south on a Buffalo Geological Society four-day fossil trip led by Jerry Bastedo. Our first quarry stop on a pleasant sunny Friday morning was in southeast Indiana at the Napoleon Quarry in Ripley County. It was a great site, but for me it might have been all that much better had I done a little research before the trip. But better late than never and here is what I have since learned.

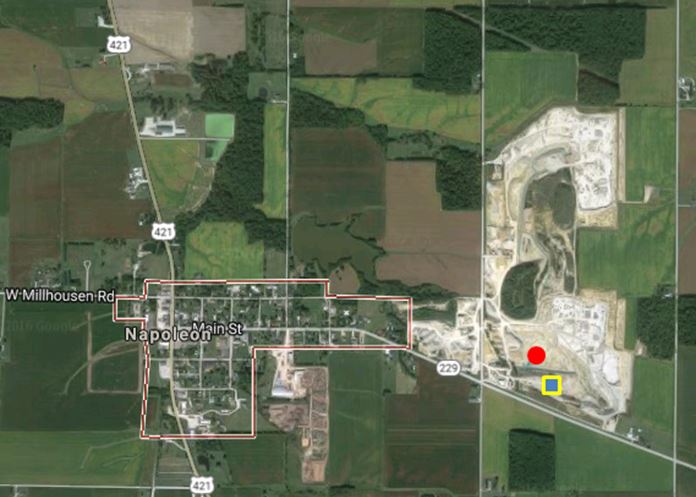

- An aerial view of the Napoleon Quarry just ½ mile east of the town center. The cover photo above was taken from the red circle towards the south.

The Napoleon Quarry, operated by New Point Stone Co., produces aggregate and limestone/dolostone products from the Lower Silurian Brassfield limestone and the overlying Osgood Member of the Salamonie Formation. However, upon arrival, it was pointed out that a drainage ditch had been cut into the uppermost Ordovician Whitewater Formation shale units beneath the carbonates and that significant fossil material could be found there. I heard that and headed for the piles of excavated shale that were weathering adjacent to the drainage ditch.

Those of us clamoring over the spoil piles in this lowest level were not disappointed. Small, but complete well-formed brachiopods were strewn about. The mineralized brachs were more resistant than the surrounding shale and could be scavenged easily as they lie atop the spoil piles.

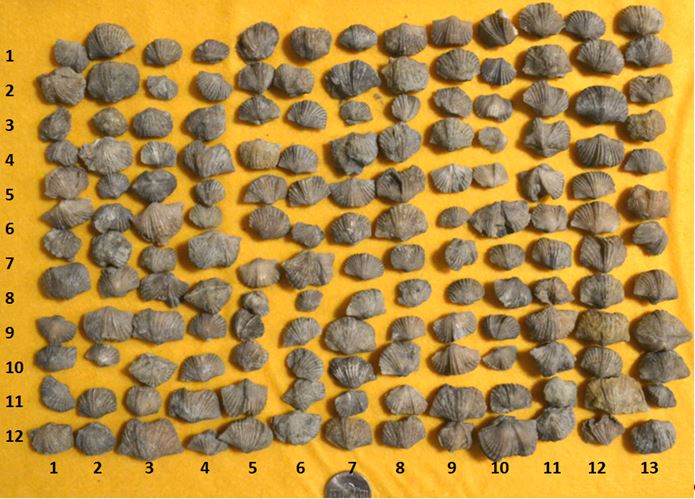

Interestingly, these abundant brachiopods were assigned to the genus Platystrophia until a definitive study of Silurian brachiopod genus (Zuykov and Harper, 2007) showed that this brachiopod from the Order Orthida deserved a separate genus. They are now reassigned to the genus Vinlandostrophia based on differences in shell morphology. We likely collected several different species with the dominant one being Vinlandostrophia clarksvillensis (Views of the Mahantango, 2011).

In addition to the ubiquitous brachiopods, rugose corals and very interesting well-formed finger-shaped bryozoa were also abundant in the Ordovician spoil piles. It was a collecting bonanza.

When we reassembled at the cars around noon to move on to a quarry in St. Paul, Indiana, I learned that others who had ventured into the higher spoil piles of the Silurian Osgood Member of the Salamonie Dolomite had done well also. In fact some had done very well indeed. They had collected numerous cystoids on the larger piles of material from the overlying Silurian carbonates.

Cystoids are a class of extinct echinoderms that attached to the seafloor by stalks. They resemble crinoids, but had an ovoid rather than a cup shaped body. The most distinctive feature of cystoids is the presence of numerous pores on each of the rigid pentagonal plates that comprise the rigid skeleton protecting the body. These pores can be seen on many of specimen in the photos below.

References:

Frest, T.J., et. al, 2011, The North American Holocystites Fauna (Echinodermata: Blastozoa: Diploporiote): Paleobiology and Systematics, Issue 380 of Bull. of Amer. Paleontology, 142 p.

Views of the Mahantango, 2011, Vinlandostrophia from Napoleon, website blog

Wikipedia entry on Cystoids

Zuykov, M. A. and Harper, D. A. T., 2007, Platystrophia (Orthida) and new related Ordovician and Early Silurian brachiopod genera. Estonian J. Earth Sci., v 56, p 11-34.

And finally, how many Vinlandostrophia did I collect?

- These are the same Vinlandostrophia brachiopods shown in the earlier photo. BUT, now it is a simple math problem to determine how many I collected !