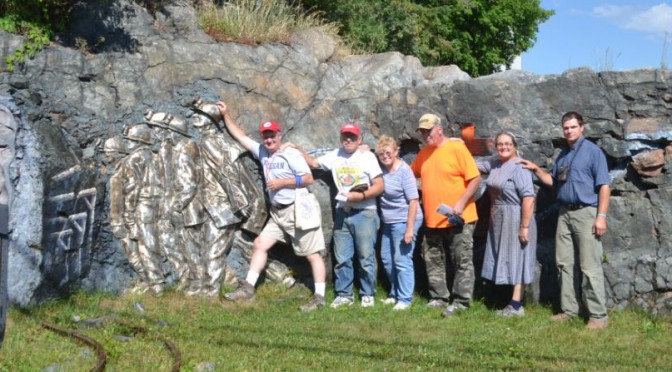

During the third week in July, seven WCGMC members spent 7 days and 6 nights collecting in Ontario. The first three days in Cobalt, Ontario are summarized here. Part 2, three days near Eganville, will be reviewed in a subsequent entry. Modified from August, 2015 WCGMC newsletter article.

From its discovery in 1903 until around 1920, Cobalt, Ontario was a hotbed of silver mining and the center of Ontario’s economic mining industry as over 10,000 inhabitants opened more than 100 mines in search of silver. Over 100 years later, and for 2 days in July, 2015, seven eager rockhounds from WCGMC followed in the old timers footsteps.

The miners of the early 20th century faced brutal winters, devastating fires, contaminated water, and, in 1909, a typhoid epidemic that hospitalized 10% of the mining district’s inhabitants killing over 100 people. By comparison, one hundred years later, the seven savvy rockhounds who visited mine dumps and mill sites from perhaps 8 of the old mines had to endure mosquitoes, black flies, sunburn, and restaurants that did not serve lemonade or Mountain Dew.

Despite these subtle environmental differences, the objective of the groups was the same: find silver. History tells us that the former group was more successful. In 1908, 10% of the world’s yearly silver production was from Cobalt, and all told over 450 million ounces of silver has been recovered for the district. This places the district as the 4th largest silver producing district in the world. By comparison, the seven intrepid modern mining warriors found a bit of silver running through thin veins of diabase host rock in two boulders in two separate locations.

BUT, we did find plenty of “cobalt bloom”, the pink cobalt arsenate mineral erythrite (Co3(AsO4)2·8H2O) that prospectors used to hone in on silver-bearing veins. This surface alteration product signaled riches below. The theory goes that migrating hydrothermal solutions rich in the elements cobalt, nickel, arsenic and silver found the chemical conditions afforded by cracks and fissures in the large diabase dikes and sills of the Cobalt region to be just right to precipitate their unusual contents. Often accompanied by calcite, these veins could carry upwards of 10-20% silver with equal amounts of cobalt and less amounts of nickel. The lucky miner found one thick enough to mine. The unlucky rockhound, well he had to buy his.

In addition to native silver, the primary minerals in the veins are cobalt and nickel arsenides, minerals such as cobaltite (CoAsS), skudderudite (CoAS3), safflorite (CoAs2), and nickeline (NiAs). We found all of these, but often the shiny metallic cobalt minerals are massive and intergrown such that identification is difficult. The term smaltite has been historically applied to intergrown cobalt arsenides.

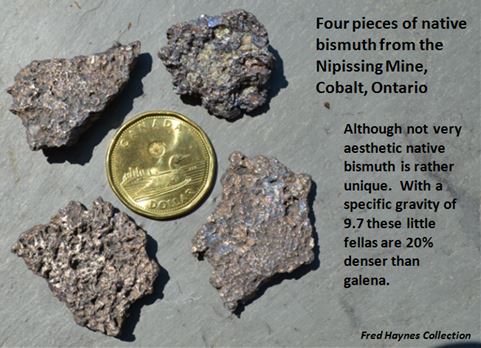

On our day in Cobalt we visited mines with names like Nipissing, Silver Miller, Hargreaves, Beaver, Timiskaming, and Cobalt Lode and collected on the large dumps of each. But our biggest break came when a young local rockhound (well, younger than most of us and certainly more local) happened to stop to see how we were doing when were collecting at the Cobalt Lake Mine quite close to town. Turns out he was a diamond driller on night shift at a gold exploration region towards Timmins to the north. We told him we were doing fine, and then he showed us the back of his pick-up and we realized we were not exactly doing fine. But he fixed that selling up many specimens at very fair prices. I cannot tell a lie, the piece pictured above is one of my purchases when he revisited us later the following evening in our motel with more samples. These included:

Most silver seekers on the Cobalt dumps, roads, and mill sites claim that a metal detector is the tool of choice. We had one and used it, but all we could find with our tool was metal nails, pipe pieces, and an occasional drill bit. Naturally we took those too!

The 3rd and 4th cores from the top are interesting rocks. They are from the Gowganda tillite, a conglomerate that was formed by glaciation during the middle Precambrian, more than 2,300 million years ago, or 2.3 billion years if you prefer. The pink and rounded granite cobbles appear to be floating in a varved lithified clay matrix, the result of rocks dropped into mud during the retreat and melting of continental glaciations. Unlike the modern glacial tills we are familiar with in upstate New York these sediments were then buried deeply and lithified into conglomerate-like rocks. The Nipissing diabase dikes (vertical) and sills (horizontal) which host both the Cobalt and Gowganda silver, cut through both Archean greenstone rocks and the tillite approximately 2,200 million years ago. The fifth horizontal core from the top and the smaller diameter cores to the left are diabase, a subvolcanic igneous rock comprised mostly of plagioclase and pyroxene and the host for most of the silver-bearing veins.

We took a break from collecting in the afternoon to visit the Cobalt Mining Museum to drool on the silver specimens and learn a bit about the history of a fascinating mining district from an interesting 30 minute movie and six rooms of exhibits.

On our second day in Cobalt, we ventured about 100 klicks east (klicks are kilometers in Canada speak) to the mining district of Gowganda. Similar in mineralogy to Cobalt, but working under the assumption of wandering the path less followed, yours truly considered it might be a good idea to venture from the main district in the hunt for riches. We did find one fine grained boulder with splotches of silver at the Miller Lake O’Brien Mine. The boulder broke to expose more so each of us could claim a piece, but overall the dumps at Cobalt were larger and pinker (i.e. more erythrite to excite our senses). We did find more core, a little copper mineralization (chalcopyrite and even a little covellite) that we did not see at Cobalt. And lots and lots and lots of drill core of all sizes.

After two full days of collecting and 3 nights in Cobalt, we loaded up our rocks and pointed our caravan towards Eganville. In a subsequent posting you can learn what we found there.

References:

Adamowicz, M., 2014, Exploring Cobalt: The Historic Silver Capital of Canada, http://www.mindat.org/article.php/1398/Exploring+Cobalt+The+Historic+Silver+Capital+of+Canada

Cobalt Mining Legacy, various pages from the website http://www.cobaltmininglegacy.ca/index.php

Sabina, A.P., 2000, Rocks and Minerals for the Collector: Cobalt-Belleterre-Timmins, Ontario-Quebec, Geol. Survey of Canada Misc. Rept. #57.